If 25 million daily passengers can move under one roof, why can’t soldiers, sailors, and pilots fight under one command? Theatre commands may be messy, but delay could be fatal.

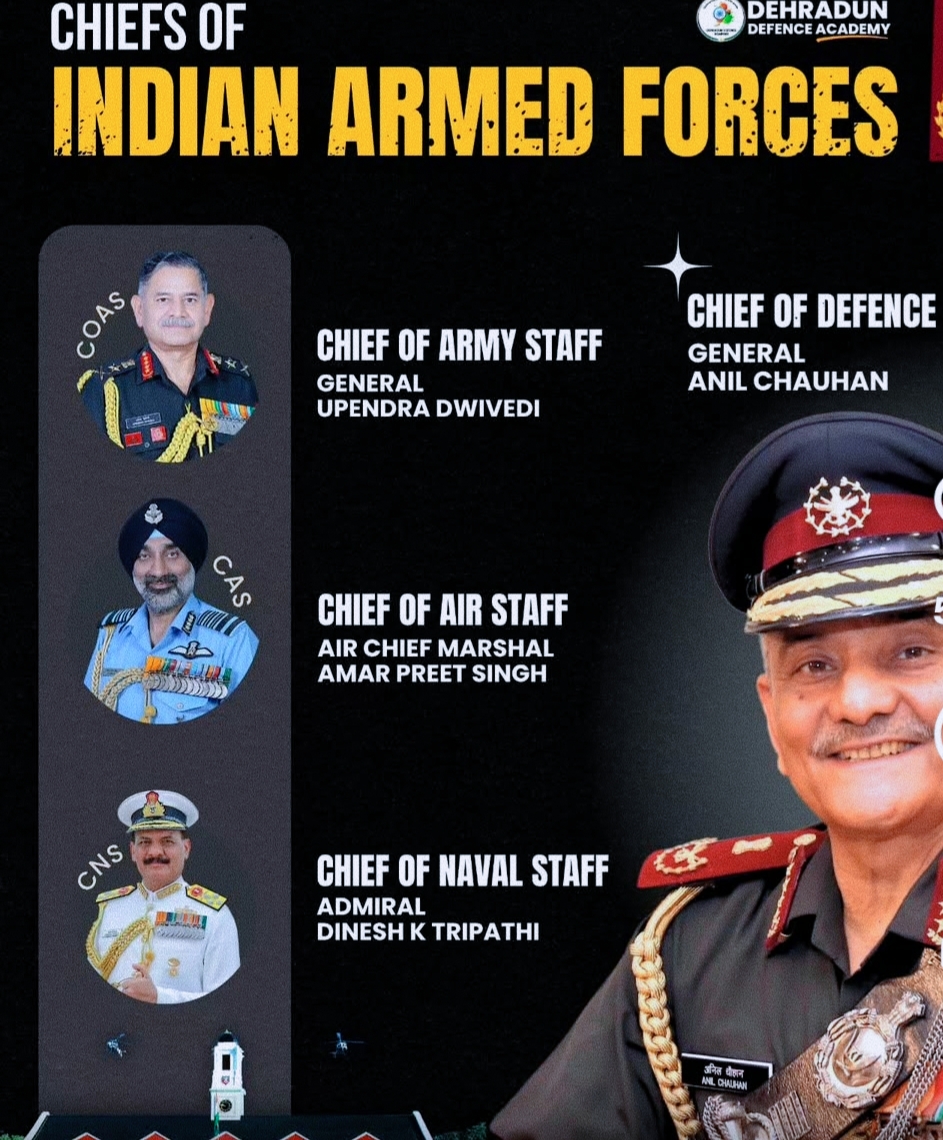

Ever since the Prime Minister’s 2019 announcement and the appointment of General Bipin Rawat as India’s first Chief of Defence Staff, the word “theatre” has been buzzing through mess halls, think tanks, and parliamentary corridors. What began as a strategic nudge to modernise joint war-fighting has repeatedly turned into a political and professional lightning rod — more so after General Rawat’s tragic death, which stalled momentum. The debate flared again recently when the Air Force chief publicly questioned the idea, reminding everyone that theatre commands are not merely an organisational tweak but a seismic shift in how the armed forces conceive war.

So what is a theatre, and why does it matter? Think of a theatre of war as a single, integrated command responsible for land, sea, and air operations across a geographic front — an idea that matured during World War II when simultaneous campaigns in Europe, North Africa, and Asia demanded unified planning and execution. The failure to coordinate can be catastrophic: history is littered with examples, from the Japanese split between army and navy at Midway to coordination breakdowns that blunted effectiveness and cost lives.

India’s own wake-up call was Kargil. In 1999 the Army engaged first, the Air Force followed later, and the Navy entered the fray even later — a staggered response that exposed seams. That same diagnosis produced recommendations over decades: fewer, leaner theatre commands replacing a sprawling mosaic of 13 separate service commands, with theatre commanders empowered to marshal all required assets. The Andaman and Nicobar Command was designed as a laboratory for this integration; the Navy has often been a vocal proponent and planner for moving beyond stovepipes.

But integration threatens existing power structures. The Air Force’s unease — that slicing aerial assets into multiple theatre “packets” would dilute strategic reach and leave each theatre with only a sliver of airpower — is not merely turf protection. Aerospace is inherently indivisible in doctrine: strategic strikes, air superiority, and deterrence require mass and coherence. Senior aviators argue that breaking the sword into pieces risks turning a precision instrument into a blunt tool that cannot deliver the rapid, strategic effects they prize.

Proponents counter that theatre commands don’t mean abandoning an aerospace viewpoint. Component commanders — specialists from each service — would still manage specific capabilities under a theatre commander’s operational control. The Department of Military Affairs and the CDS would set overarching force allocation and doctrine in New Delhi; theatres are about operational unity at the “sharp end,” not chaotic decentralisation. The idea is corporate in logic: when cross-functional teams report to a single operational head, friction is replaced by faster decisions and clearer accountability.

This is where India’s own Railways provide a surprisingly relevant analogy. Every department in the Railways — from engineering to signalling, from accounts to operations — reports to the Divisional Railway Manager at the grassroots level, and to the General Manager at the zonal level. These field leaders exercise unified administrative and operational authority over disparate branches, ensuring trains run on time and infrastructure is maintained.

Bureaucratic silos still exist, but they converge at the point of decision-making. Nobody asks whether the engineering wing or the commercial wing should “lead” — they all serve under the same operational umbrella. The result is coherence, accountability, and speed.

Why not apply the same model to the military? Instead of 17 separate service commands competing for resources and recognition, imagine a leaner map: Western, Eastern, Northern, Southern theatres, with a central zone near Delhi for strategic coordination. Each theatre commander would have the operational control of land, sea, and air assets in his or her domain, reporting upwards to the CDS and the political leadership. Wartime decisions would be swifter, responsibilities clearer, and one-upmanship minimized. In peacetime, too, synergy in planning and procurement would save resources and reduce duplication.

Politics, of course, amplifies every professional debate. Theatre commands will erase or transform some senior appointments — a delicate realignment of prestige and perks that no service chief relishes. Timing matters too. An assertive political leadership committed to push reforms can make them happen; without political will, committees proliferate and inertia wins. Six years after the CDS post was created, phase two of reforms — theatre commands — hangs in that political balance. Delay breeds doubt; doubt breeds recalibration; recalibration risks collapse of momentum.

Comparisons with the United States or China are both instructive and misleading. Yes, many modern militaries use theatre structures; no, we should not uncritically copy foreign templates. India’s theatres would be designed for its borders and maritime approaches, not global power projection. The goal is pragmatic: better deterrence, faster decision-making, and efficient use of scarce resources tailored to India’s geography and threat perceptions.

The truth is that the theatre debate is less about importing models and more about domestic reform: trimming redundancy, clarifying command lines, and ensuring India’s armed forces fight as one when called upon. Whether the country chooses to pivot now or again pause for committee reports, the stakes are the same — future wars will not wait for organisational comfort.

The Indian Railways have shown us that unity of command in complex, sprawling systems is not only possible but efficient. If trains carrying 25 million passengers a day can run under an integrated model, surely an institution tasked with national survival deserves the same clarity. Reform is uncomfortable, but armies that refuse to adapt often pay the highest price. If political leaders summon courage and the services temper pride with professionalism, India can finally build theatre commands tailored to its unique geography — a reform that could reshape deterrence and protect generations to come.

Visit arjasrikanth.in for more insights

2 responses to “If Railways Can Theatre, Why Can’t the Generals?”

Good Mornings .

National security has transcended beyond just the defence forces in terms of Army ,Navy and the Airforce. It now.includes Space , Intelligence and cybersecurity and requires complex multi domain operations to be undertaken in short reaction cycles Therefore integrating armed forces on organisational patterns of world war times will.be a retrograde step. Also complexity and short time cycles demand joint planning and operational structures with representatives from all agencies that form part of National security and an appropriate decision-making authority . Conduct of Operation Sindoor gives us important organisational lessons.

may be comparing war fighting structures with Railway routine operations May not be a very good simile .

LikeLike

We must compare apples with apples n not with oranges. Unlike trains which run on the ground, ships (Navy) & aircrafts (Air Force) don’t run on the ground. Authors suggestion is akin to merging dept of surface transport, ministry of railways, ministry of shipping & ministry of civil aviation. Though I may personally support the Idea of Theatre command concept, it’s advisable to leave the comments n suggestions to the people who spent decades in the Armed Forces. I think if an Armed Forces officer gives suggestions on the restructuring of the Indian Railways, it’s not appreciated by the people from the railways.

Air Vice Marshal Subhash Babu VSM Retd

LikeLike