India’s income tax system is endlessly argued over, yet rarely interrogated at its philosophical roots. Born in 1860 as an emergency levy to fund imperial control after the 1857 revolt, income tax was never meant to advance equity or development. It was a tool of extraction—simple, coercive, and blind to context. More than a century and a half later, independent India still operates within this colonial fiscal grammar: modernised, digitised, but conceptually unchanged. The heretical question is unavoidable now: what if the real reform is to tax spending, not earning?

From the outset, income tax in India prioritised administrative convenience over justice. It targeted visible incomes—salaries, professions, commerce—while leaving land and agricultural wealth largely untouched. The 1886 exemption of agricultural income was not pro-farmer benevolence but elite protection, a distortion that survives to this day. War-time surcharges and the 1922 Act hardened this structure. Independence did not dismantle it; it merely reassigned the collector.

Post-1947, the moral assumption remained intact: income equals ability to pay. The 1961 Act canonised this belief in an imposing legal edifice. During the high-socialist decades, this logic turned punitive. Marginal rates touching 97.75 percent in the early 1970s did not produce equality; they produced evasion, black money, and flight of capital. The state did not redistribute wealth—it criminalised ambition. Liberalisation corrected the symptoms—lower rates, better compliance, digitisation—but not the underlying philosophy. We still tax effort more than outcome.

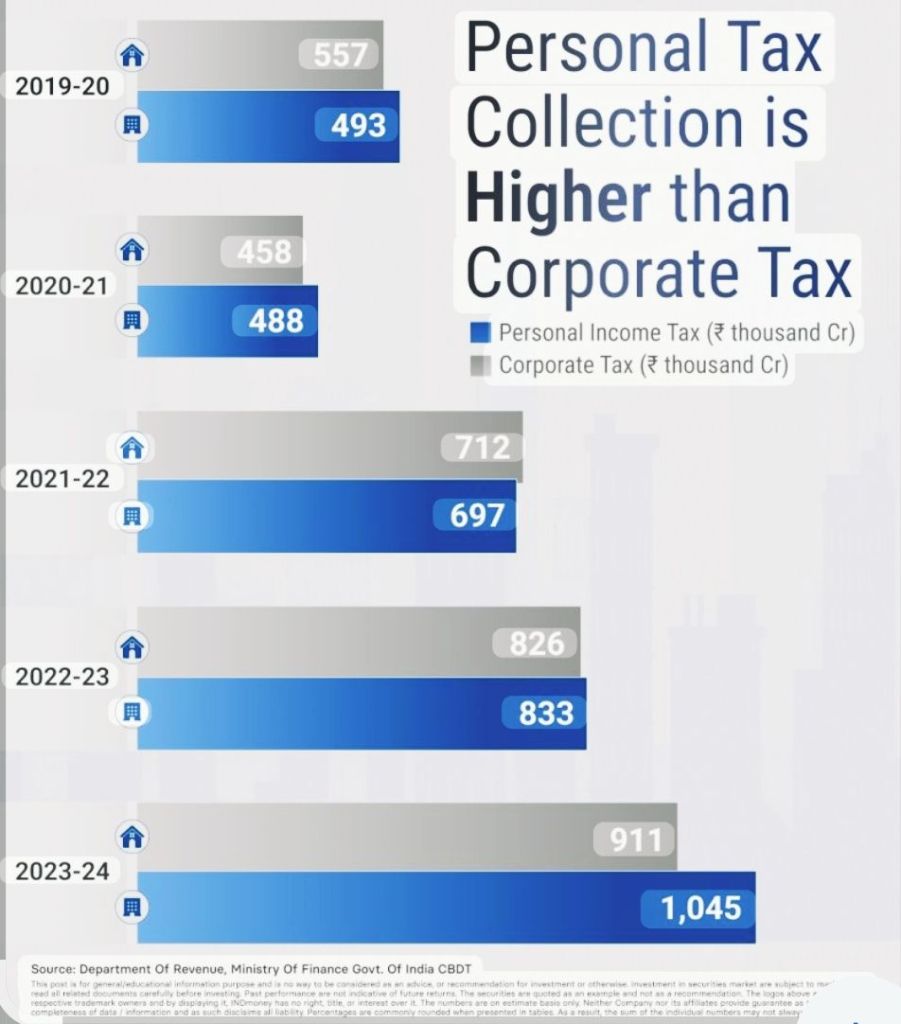

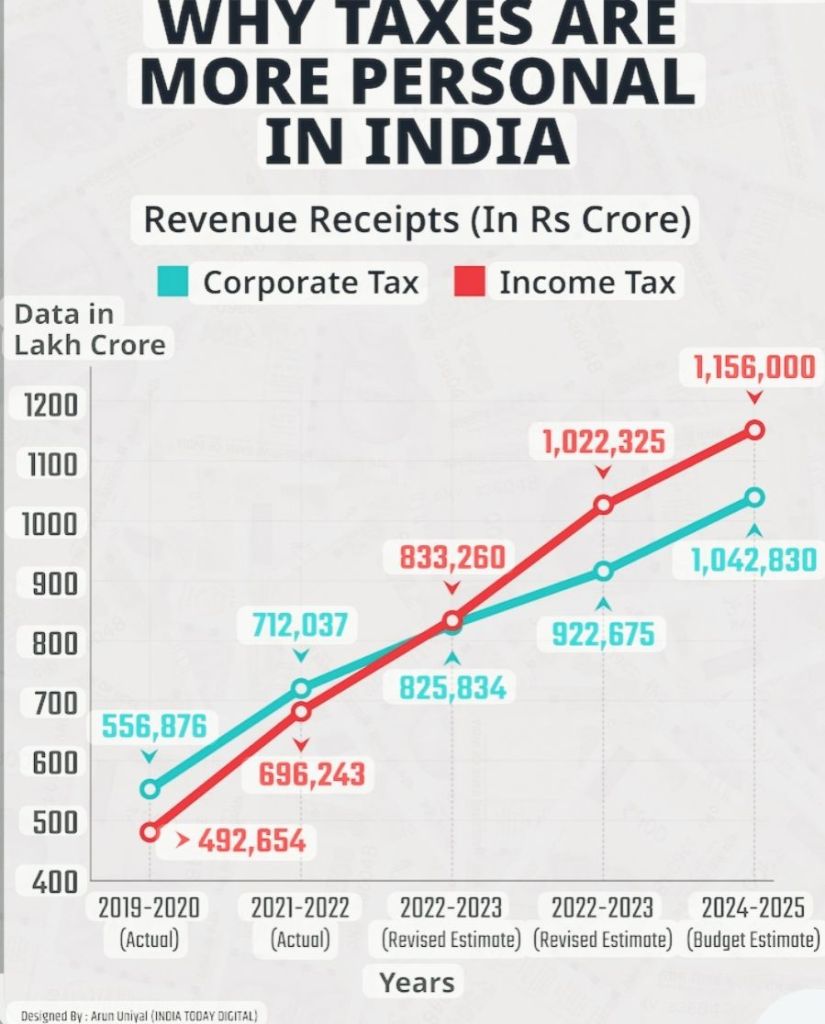

Today, the contradictions are glaring. Barely 7 percent of Indians file income tax returns. Direct taxes hover around 6 percent of GDP. Meanwhile, consumption taxes—especially GST—generate nearly a third of central revenues. India already functions as a consumption-tax state while pretending to be an income-tax republic. This mismatch breeds resentment and distortion: compliant salaried earners carry the load, while vast volumes of spending remain lightly scrutinised. Production is penalised; opacity is rewarded.

Expenditure taxation inverts this logic. It taxes what is taken out of the economy, not what is put into it. Save more, invest more, consume less—and your tax liability falls. Conceptually, it is cleaner: income minus savings equals consumption, and consumption is taxed. It dissolves many of income tax’s chronic pathologies—endless disputes over capital gains, depreciation, valuation, and the metaphysics of “income character.” For a country seeking higher savings, deeper capital formation, and long-term growth, the alignment is obvious.

India has tested this idea before. In 1958, Nicholas Kaldor’s expenditure tax experiment collapsed within four years, defeated by weak administration and a cash-dominated economy. But that India is gone. Today’s economy runs on UPI, Aadhaar, GSTN, and digital exhaust. Ironically, it is now easier to trace how people spend than how they earn. Consumption has become more visible than income.

The standard objection is regressivity. Poor households consume most of what they earn. But regressivity is a design choice, not a fate. Expenditure taxes can be made progressive through exemptions, rebates, luxury thresholds, and direct transfers. GST itself is regressive in isolation, yet politically sustained through welfare offsets. Meanwhile, income tax’s supposed progressivity collapses in practice when wealthier taxpayers defer, disguise, or export income. Moral superiority on paper means little in an evasive reality.

A sudden abolition of income tax would be reckless. But a phased, hybrid transition is not radical—it is rational.

Optional expenditure-based regimes, expanded savings deductions, cash-flow taxation for businesses, and immediate expensing of investment can gradually shift the burden from earning to spending. Over time, India could move toward taxing conspicuous, carbon-heavy consumption more heavily than labour and productive investment.

This is not merely a fiscal tweak; it is a civilisational choice. Income tax entered India as an imperial instrument of control, not a developmental ethic. Treating it as the moral centre of taxation is intellectual inertia masquerading as prudence. A confident, digital, investment-hungry India should tax lifestyles more than livelihoods, shopping carts more than salary slips. The future of taxation lies not in punishing effort, but in pricing consumption—and finally unlearning the fiscal habits of empire.

Visit arjasrikanth.in for more insights