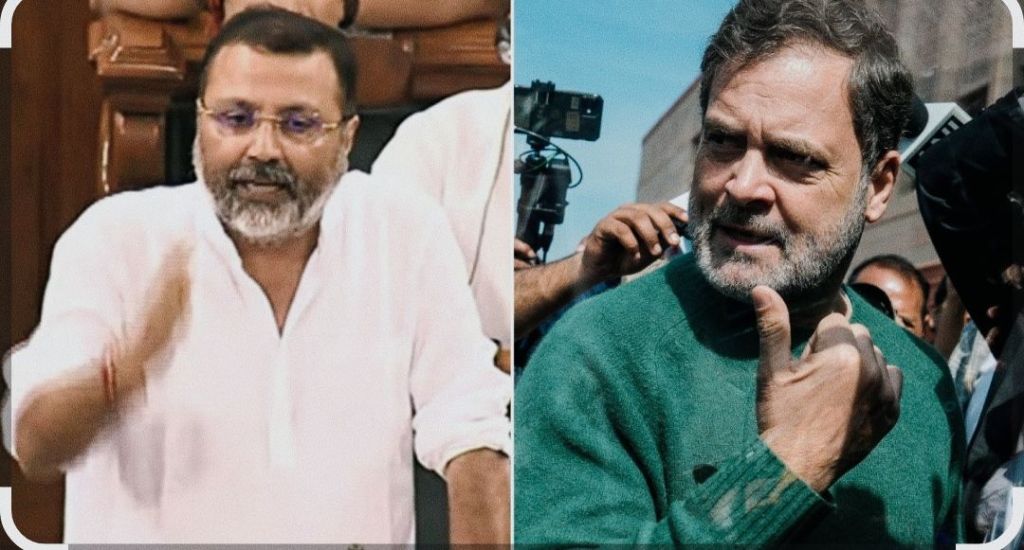

The Lok Sabha stands at the edge of a constitutional precipice. A substantive motion moved by Nishikant Dubey seeks nothing less than the expulsion of Rahul Gandhi, the Leader of the Opposition, along with a lifetime ban on his candidacy in future elections. What is unfolding is not routine parliamentary friction. It is a confrontation between majoritarian authority and the institutional sanctity of dissent—an inflection point that may redefine the grammar of India’s parliamentary democracy.

A substantive motion is among the most consequential instruments in legislative procedure. Unlike procedural or subsidiary motions that facilitate discussion, it is a self-contained proposal seeking a definitive decision of the House. If adopted, it becomes the binding will of Parliament. Historically, such motions have been invoked sparingly and in exceptional circumstances. The expulsion of ten MPs in the 2005 “cash-for-query” scandal followed damning evidence of corruption. The removal of Indira Gandhi in 1978 was framed as a breach of privilege and contempt of the House. More recently, Mahua Moitra faced expulsion after an Ethics Committee inquiry. Even Gandhi’s own 2023 disqualification arose from a judicial conviction later stayed by the Supreme Court—not from a direct parliamentary vote.

The present motion marks an escalation of an altogether different magnitude. It does not merely seek censure or temporary exclusion. It proposes political extinction through a lifetime electoral bar—an extraordinary demand without clear precedent in India’s parliamentary history. Such a sanction would shift disciplinary action from corrective to terminal, from institutional rebuke to existential erasure.

The allegations underpinning the motion are expansive and politically charged. They include claims of destabilizing the nation, collusion with foreign foundations, and defaming national institutions. A particular flashpoint has been Gandhi’s reference in Parliament to unpublished material attributed to former Army Chief General M.M. Naravane concerning the 2020 India–China border standoff. By framing parliamentary speech as national sabotage, the motion collapses the boundary between critique and subversion. The language of “anti-India forces” and systemic destabilization reframes adversarial politics as a security threat.

Procedure now rests substantially in the hands of the Speaker. The notice may be admitted, rejected, or referred to a committee such as the Privileges or Ethics Committee. Should it reach the floor, arithmetic favors passage given the ruling coalition’s majority. Yet parliamentary legality does not automatically confer constitutional wisdom. The deeper question is whether punitive authority, though procedurally valid, may be exercised in a manner consistent with the spirit of deliberative democracy

For opposition politicians, the stakes are immediate and profound. The office of the Leader of the Opposition, recognized under the 1977 statute governing its status and allowances, embodies the institutional legitimacy of dissent. To expel its incumbent on grounds rooted primarily in political speech risks transforming opposition from constitutional necessity to conditional tolerance. A lifetime ban would create a new threshold—punishment not merely for criminal conviction or ethical breach, but for assertions made within the chamber itself.

The potential chilling effect cannot be understated. Parliament is designed as a theatre of accountability, where scrutiny of executive power must be rigorous to be meaningful. If robust criticism—particularly on matters of national security or executive conduct—becomes grounds for expulsion, members may internalize caution. Self-censorship, rather than vibrant deliberation, could become the norm. Over time, this alters institutional culture, privileging restraint over candor and conformity over confrontation.

Yet history offers a counterintuitive caution. The expulsion of Indira Gandhi in 1978, intended to marginalize her, instead catalyzed political resurgence, culminating in her return to power in 1980. Parliamentary punishment can sometimes elevate a political adversary into a symbol of resistance. Should this motion pass, it may consolidate Gandhi’s stature among supporters who perceive the action as majoritarian overreach. If it fails, the mere attempt will nonetheless recalibrate the balance of parliamentary power, signaling that disciplinary tools may be deployed in intensely partisan contexts.

For the ruling establishment, the calculus extends beyond immediate assertion of strength. Democracies are sustained not by numbers alone but by norms that distinguish between contestation and annihilation. Majorities govern; they do not extinguish the minority’s voice without risking institutional backlash. The use of a substantive motion against the principal opposition figure underscores confidence in numerical superiority. But it simultaneously tests the elasticity of democratic restraint.

The consequences therefore transcend one leader’s career. They touch the evolving character of India’s parliamentary order. If expulsion and lifelong disqualification become conceivable responses to political speech, future oppositions—regardless of party—will operate within a narrower corridor of safety. Precedents forged in moments of partisan advantage may outlive those who create them.

Ultimately, this debate is less about Rahul Gandhi and more about the architecture of dissent in a majoritarian era. Parliamentary privilege exists to safeguard the dignity of the House, not to shield the government from criticism. The constitutional compact presumes a loyal opposition—loyal not to the executive, but to the Republic itself. Whether the Lok Sabha chooses punitive finality or institutional restraint will shape not merely an individual’s trajectory, but the resilience of India’s deliberative democracy for years to come.

VISIT arjasrikanth.in for more insights