India often presents itself as a lightly taxed economy, but this narrative collapses under scrutiny. Fewer than 10 percent of Indian households fall within the income-tax net, yet this small, highly compliant group carries a disproportionate share of the fiscal burden. Over the past decade, the composition of tax revenues has shifted decisively. Corporate tax collections have declined from roughly 3.7 percent of GDP to about 3 percent, while household contributions have climbed to nearly 3.9 percent of GDP. This is not a neutral outcome of economic change; it reflects a fiscal design that finds it administratively efficient and politically low-risk to tax salaried households while leaving large reservoirs of income and wealth structurally under-taxed.

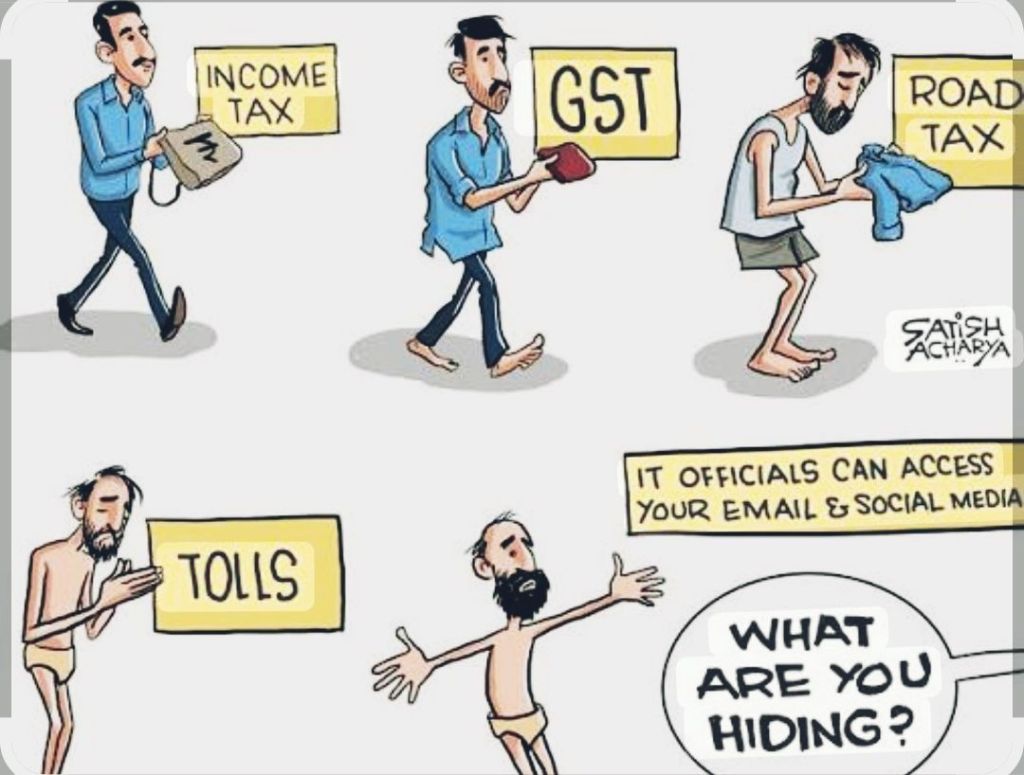

The result is a stark fiscal paradox. The poorest citizens are exempt by necessity, while significant segments of the wealthy—particularly those deriving income from agriculture, assets, or complex ownership structures—remain outside the effective income-tax net. What remains is a narrow but dependable base of urban professionals, salaried employees, and small entrepreneurs who are digitally visible, continuously traceable, and unable to opt out. For this group, taxation is not episodic or negotiable; it is constant, automated, and intrusive, woven into every paycheck and transaction.

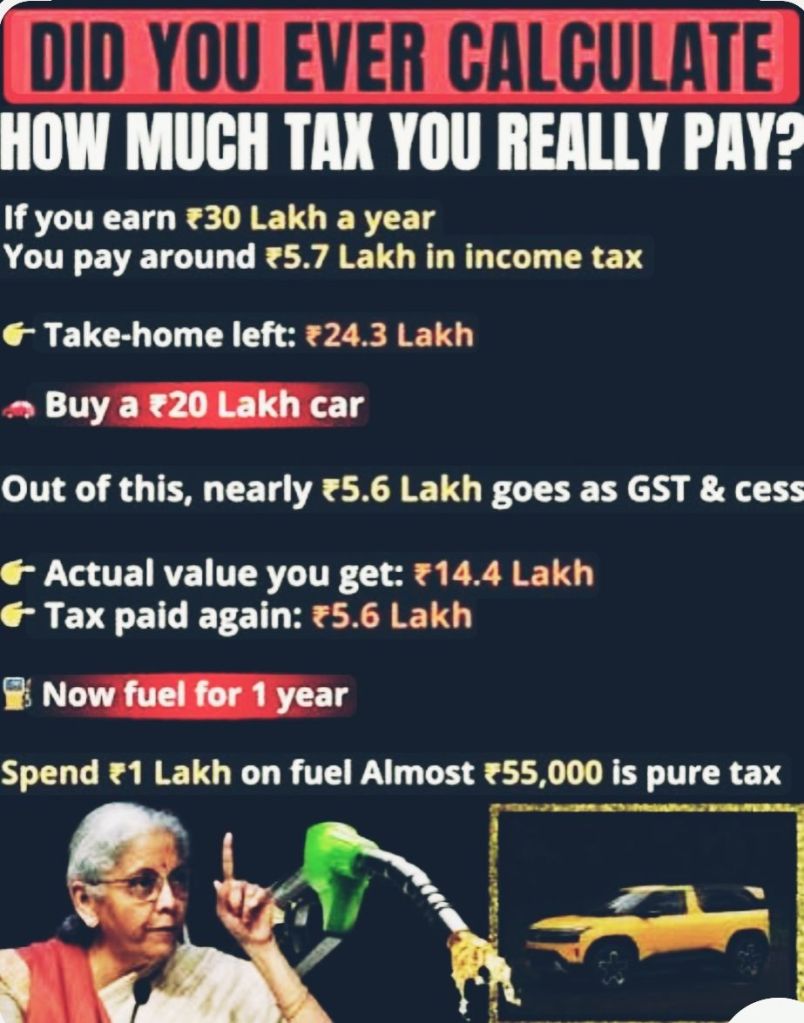

This imbalance is magnified by India’s reliance on indirect taxes, especially the Goods and Services Tax. Conceived as a neutral and efficiency-enhancing reform, GST has proven regressive in practice. Indirect taxes consume a larger share of middle-class disposable income than of wealthy households’ spending, quietly penalising everyday consumption such as fuel, transport, insurance, food services, and utilities. The burden is not only about rates but about structure. Inverted duty regimes—where taxes on inputs exceed those on final goods—are now widespread in sectors like food processing and manufacturing. Firms often pay 18 percent GST on logistics and services while collecting only 5 percent on outputs, leading to blocked input tax credits and persistent working-capital stress. These costs are rarely absorbed by businesses; they are passed on to consumers, forcing the middle class to pay twice—once as taxpayers and again as consumers underwriting systemic inefficiencies.

The bias becomes even clearer in the taxation of savings and capital markets. Retail investors pay Securities Transaction Tax on every trade and then face Long-Term Capital Gains tax on profits beyond ₹1.25 lakh. For salaried individuals earning below ₹12 lakh, this LTCG is non-rebatable, creating a real tax liability even on modest, long-term savings. The incentive structure is perverse: disciplined, transparent investment is penalised, while speculative or opaque avenues often escape equivalent scrutiny. The same logic applies to newer asset classes. Virtual digital assets are taxed aggressively on gains, while losses cannot be set off, and compliance norms designed for professional traders are imposed on small retail participants. Instead of encouraging formal savings and capital formation, the system treats financial participation as a regulatory risk.

Beyond rates and exemptions lies a deeper, more corrosive problem: complexity. India’s tax compliance burden functions as a shadow tax in its own right. Frequent filings, overlapping audits, ambiguous provisions, and discretionary enforcement raise costs for households and businesses alike. Global evidence is unambiguous—inefficient tax administration suppresses investment, discourages formalization, and erodes trust. In India, compliance anxiety has become a defining feature of middle-class economic life. The Income Tax Act, 2025, effective from April 1, 2026, captures this contradiction. While a reduction in sections and word count signals reform intent, simpler drafting does not automatically translate into a simpler lived experience. Taxpayers increasingly demand plain-language rules, reliable pre-filled returns, and predictable outcomes. In an era of advanced data analytics, approximate disclosures that trigger audits are not just inefficient; they are indefensible.

The corporate tax experience reinforces the imbalance. India’s 2019 corporate tax cut was expected to trigger a private investment surge. It did not. Corporate savings rose, but investment rates stagnated, underscoring that tax rates alone do not drive capital formation. Regulatory uncertainty, infrastructure bottlenecks, demand constraints, and policy unpredictability matter far more. Yet instead of addressing these structural barriers, the fiscal system has compensated by intensifying extraction from households, deepening the disconnect between who earns and who pays.

International experience points in a different direction. Estonia taxes corporate profits only when distributed, encouraging reinvestment. New Zealand operates a broad-based, single-rate GST with minimal exemptions, maximising transparency. Singapore exempts capital gains entirely and uses tax policy as a strategic growth instrument. Across advanced economies, the pattern is consistent: simplicity, neutrality, digital administration, and trust-based compliance. India, by contrast, has layered cesses, surcharges, exemptions, and procedural obligations onto a shrinking base—a strategy that is fiscally shortsighted and socially corrosive.

The middle class is not demanding tax immunity; it is expressing exhaustion. The demand is for fairness, predictability, and proportionality. Reducing double taxation, correcting GST distortions, easing compliance, and rebalancing the direct–indirect tax mix are not populist concessions; they are prerequisites for sustainable growth and democratic legitimacy. A tax system that relentlessly targets the visible while sparing the powerful is neither equitable nor durable. India’s fiscal future depends on a philosophical shift—from squeezing compliance to rewarding participation, from extraction to empowerment. Until that shift occurs, the middle class will remain the country’s most dependable—and most overburdened—fiscal asset.

Visit arjasrikanth.in for more insights