The Gulf of Kutch is no longer a passive indentation on India’s western coastline; it is a consciously engineered theatre of capital, power, and national ambition. Once defined by salt pans, tidal creeks, and artisanal fishing, the Gulf has been refashioned into one of the most concentrated zones of industrial wealth creation in the Global South. On its opposing shores rise two corporate architectures of unprecedented scale—the Ambani and Adani empires—whose capital, technological depth, and strategic audacity have transformed an ecologically austere seascape into a cornerstone of India’s energy security, logistics supremacy, and export competitiveness.

Geography set the stage, but intent wrote the script. The Gulf’s deep natural draft, proximity to Middle Eastern energy routes, and direct access to the Arabian Sea gave it latent strategic value for centuries. Yet potential alone does not create prosperity. Liberalisation in the 1990s unlocked private risk-taking, but it was the willingness of large Indian conglomerates to commit capital at civilisational scale that converted geography into destiny. The Gulf did not evolve organically; it was dredged, planned, connected, and embedded into global value chains with almost militaristic precision.

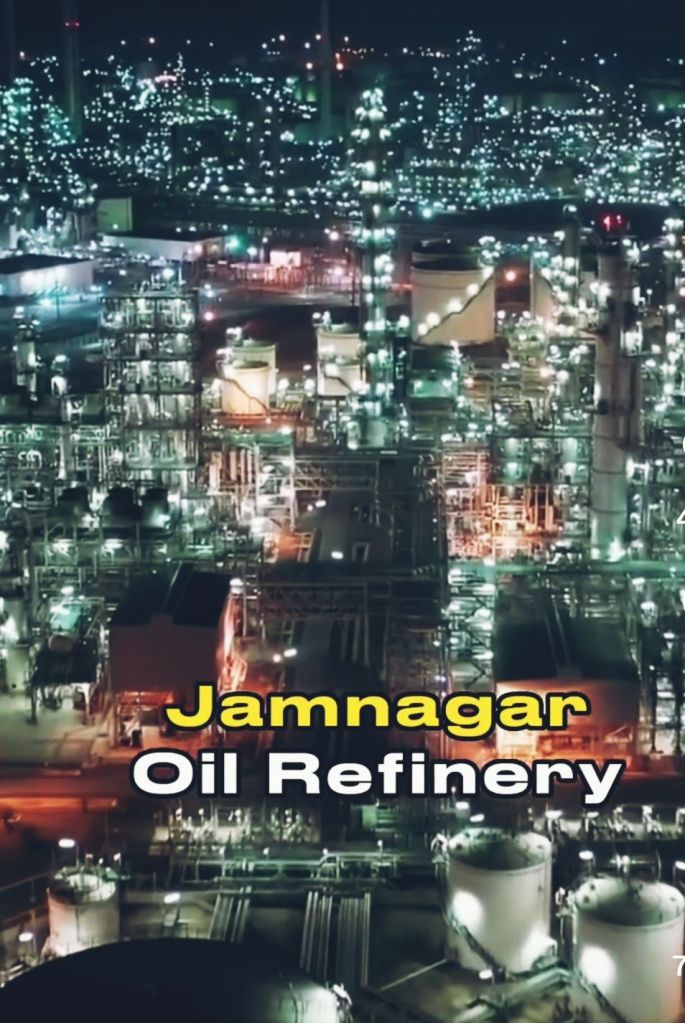

On the southern shore, Reliance Industries’ Jamnagar complex represents a feat of industrial concentration rarely matched anywhere in the world. Processing nearly 1.4 million barrels of crude oil per day, it is not merely the world’s largest refining hub; it is a masterclass in integration. Crude imports, refining, petrochemicals, polymers, textiles, and downstream manufacturing are woven into a single system that converts volatility into margin. Jamnagar’s real strategic value lies not in output alone, but in insulation—India’s ability to remain energy-secure, export-capable, and geopolitically resilient amid global supply shocks. Wealth here is measured not just in balance sheets, but in strategic autonomy.

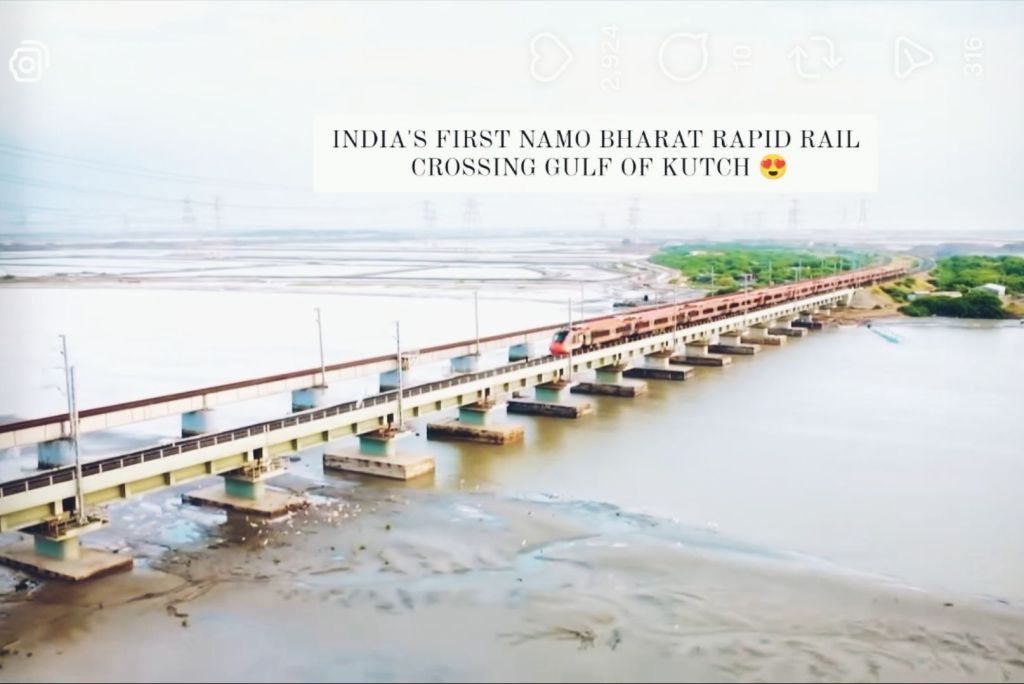

Across the Gulf, the Adani Group built a different, equally formidable engine of accumulation. Mundra Port, now India’s largest commercial port, is less a port than a logistical ecosystem. Seamlessly connected to power plants, SEZs, rail corridors, warehousing clusters, and renewable energy installations, Mundra functions as the respiratory system of North India’s economy. Coal, containers, automobiles, food grains, and increasingly, solar modules flow through its terminals with industrial choreography. This is infrastructure capitalism at scale—where control over movement, not manufacturing alone, becomes the source of enduring advantage.

Together, these twin poles have converted the Gulf of Kutch into India’s most potent industrial corridor. Cumulative investments exceeding $150 billion have generated over half a million direct and indirect jobs, while contributing close to a quarter of Gujarat’s GDP. The multiplier effects are unmistakable: townships emerging from scrubland, expressways slicing through salt deserts, and dense clusters of ancillary industries gravitating toward scale. Global capital followed—BP, Total, Siemens—not because of subsidies alone, but because size itself reduces risk and uncertainty.

This transformation, however, was not frictionless. The Gulf is ecologically fragile, hosting mangroves, coral ecosystems, and India’s only marine national park. Industrialization provoked sustained environmental litigation, civil society resistance, and anxiety among traditional fishing communities facing displacement and cultural erosion. Water scarcity, hostile terrain, and the absence of pre-existing infrastructure turned every project into a high-stakes logistical gamble. Global oil price collapses threatened refinery economics; ESG scrutiny introduced reputational risk into every balance sheet.

What distinguishes the Gulf of Kutch story is not the absence of conflict, but the capacity to absorb and re-engineer it. The Gujarat state acted less as a regulator and more as a strategic enabler—providing policy stability, aggregating land, fast-tracking infrastructure, and aligning bureaucratic incentives with long-term industrial outcomes. Technology substituted for geography: automated ports, zero-liquid-discharge plants, deep refinery integration, and world-class logistics efficiency. Environmental mitigation—mangrove regeneration, wastewater recycling, carbon-neutral commitments—evolved from compliance rituals into instruments of risk management.

Vertical integration became the final stabiliser. Ports fed power plants; power plants energised factories; factories fuelled exports. Corporate social investments in healthcare, education, and skilling were not philanthropic afterthoughts but social shock absorbers, embedding local communities into the industrial ecosystem and reducing resistance to scale.

The future of the Gulf of Kutch now sits at the intersection of green transition and geopolitical relevance. Massive investments in solar, wind, and green hydrogen aim to pivot the region from fossil dominance to clean-energy leadership. Port expansions and transshipment ambitions position the Gulf as a critical Indo-Pacific trade node. At the same time, climate volatility—cyclones, rising sea levels—forces sustainability to become a survival imperative, not a branding exercise.

Ultimately, the Gulf of Kutch stands as a living laboratory of how geography, capital, and state capacity can be fused to manufacture national power. Ambani and Adani did not merely build refineries and ports; they bent a sea into an economic engine. The unresolved question is not whether wealth was created—it unquestionably was—but whether this wealth can be sustained, equitably distributed, and defended in a century defined by climate stress and geopolitical churn. On that answer rests whether the Gulf endures as an industrial miracle or becomes a cautionary monument of salt, steel, and ambition.

Visit arjasrikanth.in for more insights