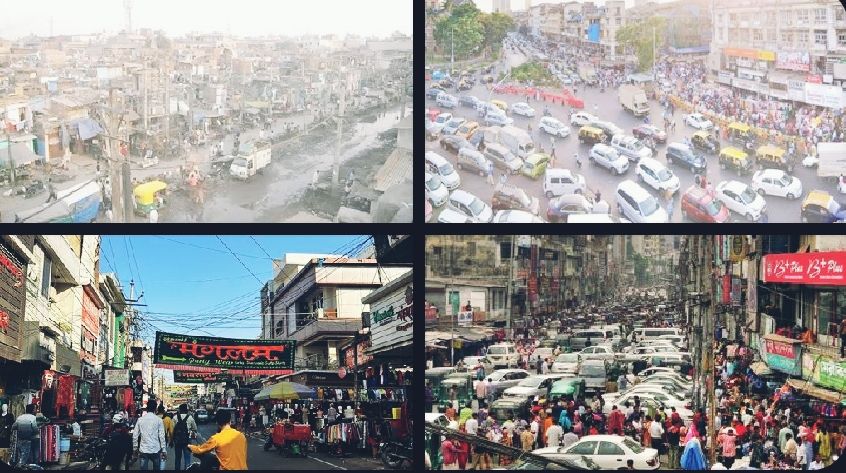

India’s cities are economic superstars with municipal wallets that would embarrass a village panchayat. They generate more than 60 percent of the nation’s GDP, attract global capital, incubate innovation, and power the services economy that keeps India visible on the world map. Yet step outside the glass towers and GDP graphs collapse into broken pavements, clogged drains, traffic paralysis, unreliable water, and shrinking public space. The phrase “rich on paper, poor on pavement” is not rhetorical flourish; it is the central truth of India’s urban condition. This contradiction is not born of ignorance or lack of ambition, but of a structural failure where money stubbornly refuses to follow responsibility.

The decay of Indian cities begins with governance that is fragmented, diluted, and politically micromanaged. Urban India is ruled not by cities but by committees: municipal corporations, development authorities, parastatals, state departments, utilities, and special purpose vehicles—often working at cross purposes. Accountability dissolves in overlapping jurisdictions, while decision-making slows into paralysis. Urban local bodies are constitutionally responsible for delivering everything from water and sanitation to roads, housing, and public health, yet they remain fiscally dependent on state governments. The 74th Constitutional Amendment promised empowered cities; what emerged instead were cities with obligations but no authority, plans but no purse, vision documents but empty treasuries.

This institutional weakness manifests brutally in infrastructure. Transport systems privilege cars over people, producing congestion without mobility and flyovers without flow. Footpaths are either absent or occupied, making walking an act of risk rather than right. Water supply remains intermittent, non-revenue water bleeds finances dry, sewerage networks are incomplete, and stormwater drains double as open trash channels until cities flood with clockwork predictability. Housing policy oscillates between unaffordable formal supply and informal slums that the city tolerates but never truly integrates. Assets are built with ceremony and then abandoned to neglect, trapped in a “build–ignore–rebuild” cycle that bleeds money without building resilience.

Urban planning, which should be the intelligence system of a city, has become its weakest nerve. Master Plans are often outdated the day they are notified, disconnected from mobility, environment, and economic reality. Enforcement is selective, corruption-prone, and politically pliable, allowing encroachments on lakes, parks, and pavements while penalising the compliant. Citizens—the ultimate users of urban space—are rarely consulted beyond token hearings. The result is cities designed for land transactions rather than lived experience, for short-term extraction rather than long-term functioning.

At the heart of this deterioration lies a fiscal scandal hiding in plain sight. All municipal bodies in India together spend barely 1.3 percent of GDP. This is not austerity; it is urban starvation. By comparison, local governments in China control nearly 25 percent of GDP spending, and in the United States, state and city governments account for about 20 percent. India’s cities carry the economic load of the nation on budgets that can barely cover salaries, electricity bills, and routine maintenance. Property taxes are politically under-exploited, user charges are rarely cost-reflective, and state transfers are uncertain and delayed. Cities earn wealth for the nation, but are denied the means to reinvest it in themselves.

The failure of municipal bonds exposes this contradiction with particular cruelty. Municipal bonds should be the natural bridge between urban growth and infrastructure finance. Instead, India’s entire municipal bond market is barely ₹4,200 crore—economically trivial for a country of this scale. This is not because cities are fiscally bankrupt. Many major municipal corporations run revenue surpluses and have shown steady revenue growth. The problem lies in weak revenue autonomy, inconsistent accounting, poor disclosure, and the shadow control of state governments that undermines investor confidence. Cities are solvent but not sovereign, creditworthy but not credible, capable of repayment but denied independence.

Globally, cities have solved problems India still debates. Singapore integrates planning, housing, transport, and finance through empowered institutions. Curitiba moves millions daily through efficient bus systems instead of chasing flyovers. Copenhagen designs streets for cyclists before cars. Medellín stitched its poorest neighbourhoods into the city through transport and public spaces, not token schemes. India knows these examples well; it cites them often, imitates them selectively, and funds them inadequately. Missions and acronyms create the illusion of progress, while the underlying fiscal architecture remains untouched.

India is racing toward a $5 trillion economy on urban legs that are visibly buckling. This is not a failure of talent, technology, or intent. It is a refusal to trust cities with money, authority, and accountability. Until urban local bodies are empowered in deed, not just in documents—through real devolution of funds, predictable revenues, credible borrowing, and citizen-centric planning—India’s cities will continue to look prosperous from the air and dysfunctional at street level. The tragedy is not that India lacks capital; it is that its cities are forbidden from touching it.

Visit arjasrikanth.in for more insights