What began as a procedural enforcement action mutated, almost overnight, into one of the most intellectually disquieting political episodes of contemporary India—a moment where laptops stood in for sovereignty, raids resembled street theatre, and the Constitution seemed to pause, unsure whether it was being interpreted or openly tested. The Enforcement Directorate’s January raids on premises linked to I-PAC, a private political consultancy advising the Congress alliance in West Bengal, were remarkable not merely for targeting a non-governmental political actor, but for what followed: a Chief Minister walking into a raid location, exiting with a laptop and files, and daring the Republic to clarify where authority truly resides.

Formally, the raids were tethered to the long-running coal smuggling case registered by the CBI in 2020, involving illegal extraction and diversion of coal from Eastern Coalfields Limited. Over time, the investigation widened to alleged hawala channels and money laundering, bringing the ED into the frame. The case was neither new nor peripheral. It had already brushed against powerful political interests in Bengal, including individuals close to the Chief Minister, making it a combustible mix of crime, capital, and influence. But until that day, it was still recognisably a legal process.

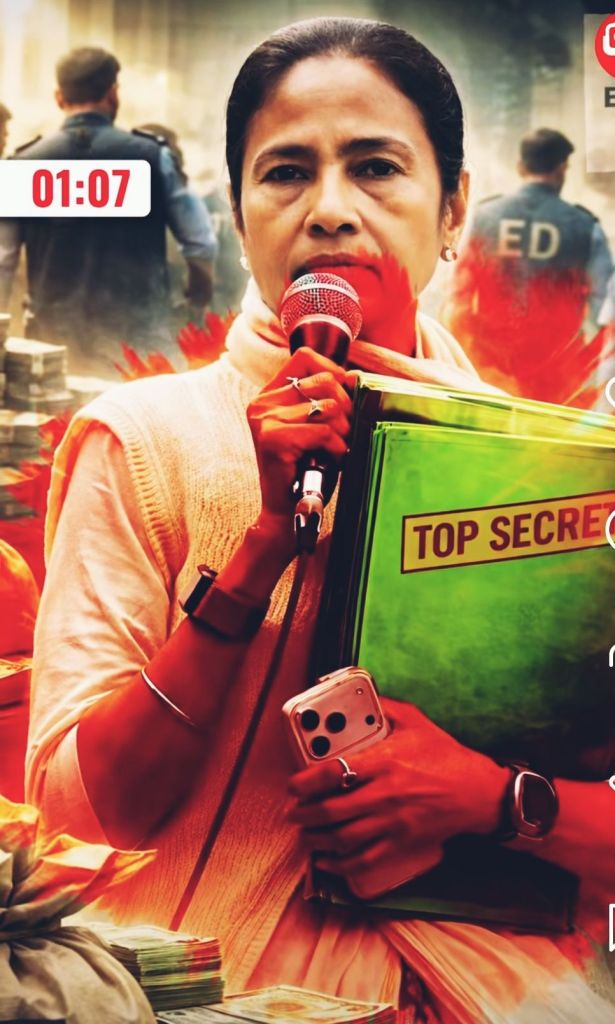

The transformation from investigation to constitutional flashpoint occurred on the ground. ED officials attempting searches reportedly found themselves obstructed—local police present, central forces stalled, and access contested. Then came the optics that altered the narrative irreversibly: the arrival of Kolkata’s Police Commissioner, followed by Mamata Banerjee herself. A sitting Chief Minister entering a raid site, staying briefly, and leaving with a laptop and a green folder—later described as confidential political strategy documents—was not symbolic defiance alone. It was a performative assertion that political authority could physically intervene in an ongoing investigation.

Banerjee’s defence was unapologetically political. She framed the raids as a covert attempt to access opposition election strategies ahead of impending polls, portraying the Centre as weaponizing investigative agencies to sabotage democratic competition. In her account, the seized materials were not evidence but intellectual property, essential to electoral fairness. The ED’s narrative could not be more different. It alleges that potential evidence was forcibly removed in the presence of senior state officials, irreparably compromising the probe. The agency’s unusually sharp language—describing the incident as a “showdown” and an act of obstruction—signals how seriously it views the challenge.

The confrontation has now ascended to the Supreme Court. The ED has invoked Article 32, arguing that its right to conduct an independent investigation has been violated by a state government. This is an extraordinary claim, reflecting how far institutional conflict has travelled. Simultaneously, the West Bengal government has mounted a multi-front response: police complaints against ED officers, a state-level probe into alleged procedural violations, public protests led by the Chief Minister herself, and a caveat in the Supreme Court to ensure the State is heard before any adverse order. Parallel proceedings in the Calcutta High Court further complicate an already crowded legal battlefield.

Stripped of personalities, the episode exposes a structural unease at the heart of India’s federal democracy. Policing is constitutionally a State subject; central agencies derive authority from special statutes that often stretch federal sensibilities. West Bengal’s withdrawal of general consent to the CBI years ago reflected a broader opposition anxiety about political misuse. While the ED does not require such consent under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, its expanding footprint has generated similar resistance. The result is legality without legitimacy, power without consensus.

Data intensifies the discomfort. Patterns in recent years show a disproportionate number of investigations involving opposition leaders, frequently surfacing near elections. Even if legally tenable, such timing corrodes public trust. Yet the counter-response—elected governments physically obstructing raids, intimidating officers, or removing material under scrutiny—does equal damage. In this collision, neither side emerges institutionally intact. Agencies appear partisan; governments appear lawless; citizens are left choosing between competing claims of victimhood.

The judiciary now stands as the reluctant referee. Its eventual ruling will resonate far beyond the fate of a laptop or a folder. A verdict favouring the State may embolden resistance to central agencies across opposition-ruled states; a verdict favouring the Centre risks normalising coercive federalism. Either way, the judgment will recalibrate the grammar of Centre–State relations.

What makes the moment genuinely unsettling is its creeping normalisation. Raids interrupted by political mobilization, investigations dismissed as electoral conspiracies, and constitutional remedies deployed as tactical weapons are no longer aberrations; they are becoming routine. When every institution is suspect and every action is politicized, governance collapses into perpetual confrontation.

The I-PAC episode is not an outlier. It is a mirror held up to a Republic struggling to decide where law ends and power begins. If restraint, institutional respect, and democratic maturity do not return to the center of public life, today it is laptops and files. Tomorrow, it may be something far more foundational that is carried out of the room.

visit arjasrikanth.in for for more insights