History is notoriously bad at recognising foresight in real time. It prefers its visionaries embalmed in hindsight, not questioned in the present. When projects are new, quiet, and underperforming by headline standards, they are rarely read as deliberate; they are dismissed as premature or flawed. That is precisely where both Mundra and Navi Mumbai Airport sit in the public imagination today. Mundra, once mocked as an overambitious port planted in a salt marsh, is now a self-sustaining, multi-million-dollar economic organism that redefined India’s logistics and industrial geography. Navi Mumbai Airport, criticised for limited flights, evolving connectivity, and a muted launch, is walking the same misunderstood path. The connective tissue is not concrete or steel, but Gautam Adani’s habit of seeing infrastructure not as a utility, but as a living commercial system designed to compound over decades. This is not one-generation thinking. It is two generations ahead, conceived early and defended patiently.

Mundra’s lesson was stark and unforgiving: infrastructure by itself creates very little value. Ports, roads, and terminals are inert unless wrapped in economic logic. Many players had land, capital, and policy support. They built assets and waited. Adani built ecosystems. Mundra succeeded not because ships arrived, but because industries followed—SEZs, power plants, rail links, logistics parks, warehouses, and jobs feeding into one another. Infrastructure was treated not as the destination but as the ignition point. That same philosophy now governs Adani’s approach to airports. Aviation, in this worldview, is merely the trigger. The real business lies in what people do with time, space, and movement. Waiting becomes monetizable, transit is curated, and every square foot is designed to earn rather than merely exist.

Mumbai Airport illustrates this philosophy in numbers rather than rhetoric. Critics complain about congestion, retail-heavy terminals, long queues, and the sense of being inside a mall. But those complaints inadvertently validate the strategy. Revenue climbed from ₹7,394 crore to ₹9,276 crore, profits rose from ₹3,447 crore to ₹4,350 crore, and retail subsidiaries swung from a loss of ₹27 crore to a profit of ₹772 crore. This is not accidental crowding; it is deliberate conversion of dwell time into economic yield. Adani Airports is not dependent on regulated aeronautical fees alone. Non-aeronautical revenue already contributes close to 50 percent and is projected to reach 70 percent by 2030. Globally, airport operators aspire to this ratio. Adani is executing it in India, where regulation is tighter and margins thinner.

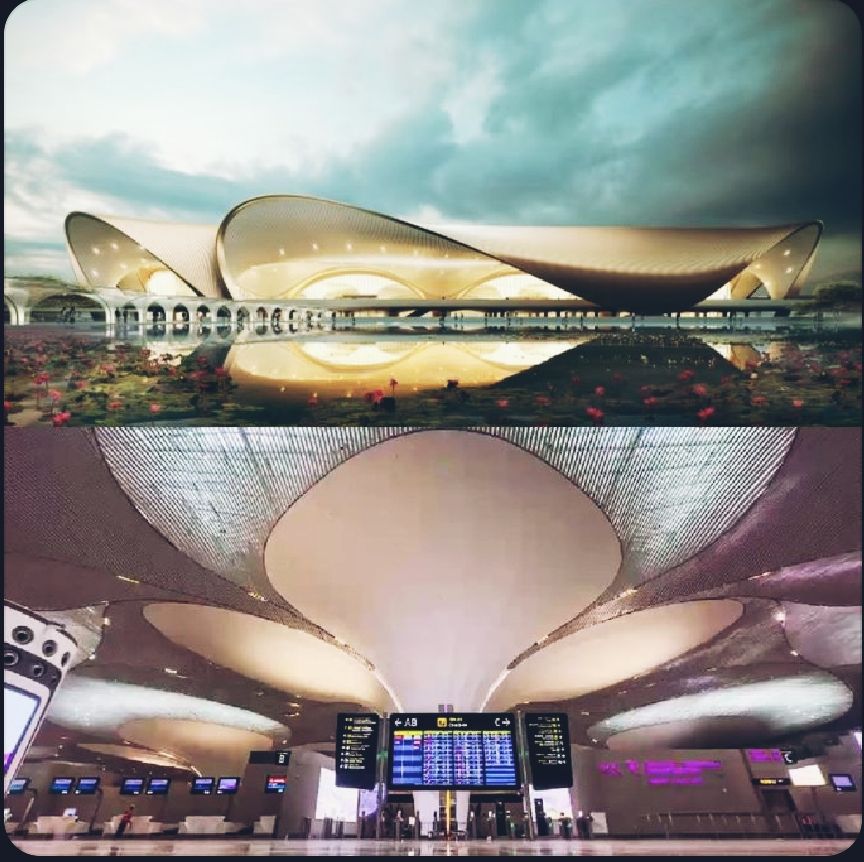

Navi Mumbai Airport is being constructed as a greenfield expression of this model—cleaner, larger, and far more controlled. Today, it operates with one runway, limited hours, and a small set of domestic routes. Road connectivity is still maturing, metro links are distant, and international ambitions remain nascent. But focusing on these teething issues misses the architectural logic. Nearly 70 percent of the planned 110 retail and food outlets will be Adani-owned brands. This is vertical integration in its sharpest form—controlling not just space, but consumption, data, pricing, branding, and customer journeys. Airports elsewhere rent shops; Adani runs ecosystems. Revenue is not hostage to flight density. It is manufactured independently of it.

This inversion—monetising first and letting traffic justify itself later—is where most organisations fail. They wait for scale before designing value. Adani designs value first and allows scale to arrive organically. Convention centres, lounges, business hubs, lifestyle zones, bookstores, food brands, and digital analytics are not decorative add-ons; they are the core business model. Navi Mumbai is not being built as a relief valve for Mumbai. It is being engineered as an aerotropolis-in-waiting, just as Mundra was never intended to be merely a port. The capital intensity is enormous, the criticism relentless, and the patience required uncomfortable—but that is the cost of being early.

None of this negates legitimate concerns. Market concentration, tariff regulation, competition, and passenger protection deserve scrutiny, especially when one group handles a significant share of India’s air traffic. Regulation exists to discipline power, and rightly so. But regulation does not invalidate vision. What Adani has repeatedly demonstrated is an ability to absorb regulatory pressure while still building commercially resilient assets. Mundra survived scepticism, litigation, and shifting policies to become indispensable. Navi Mumbai will likely travel the same arc. Sparse flights and early quiet are not signals of failure; they are symptoms of long-cycle infrastructure thinking operating in a short-attention economy.

The uncomfortable truth is that India’s next phase of growth demands builders who think beyond electoral cycles, quarterly earnings, and instant applause. Adani’s real advantage is not capital or access; it is temporal imagination. He builds today for behaviours that will emerge tomorrow. Mundra proved that such imagination, when matched with execution, can redraw economic maps. Navi Mumbai is attempting the same—not by copying global airports, but by redefining what an Indian airport can be. The runway is visible. The destination lies decades ahead. And that, historically, is exactly where transformative infrastructure has always begun.

Visit arjasrikanth.in for more insights