History has a weakness for trophies. Indore owns eight of them—gleaming, certified, globally celebrated—eight consecutive crowns as India’s cleanest city. The city became a civic fable, a PowerPoint-perfect case study in behavioural change, waste segregation, municipal efficiency, and urban pride. It was showcased as proof that Indian cities could govern themselves into modernity. Yet beneath the banners of cleanliness and the carefully staged optics of awards, the city’s most essential system—its water—was quietly rotting. In early January, contaminated drinking water killed thirteen people, including a six-month-old infant, and hospitalised more than 160. Vomiting, dehydration, bacterial infections followed in grim succession. This was not a policy lapse measured in reports; it was a public health catastrophe measured in coffins. Indore’s reckoning arrived not through rankings, but through funerals.

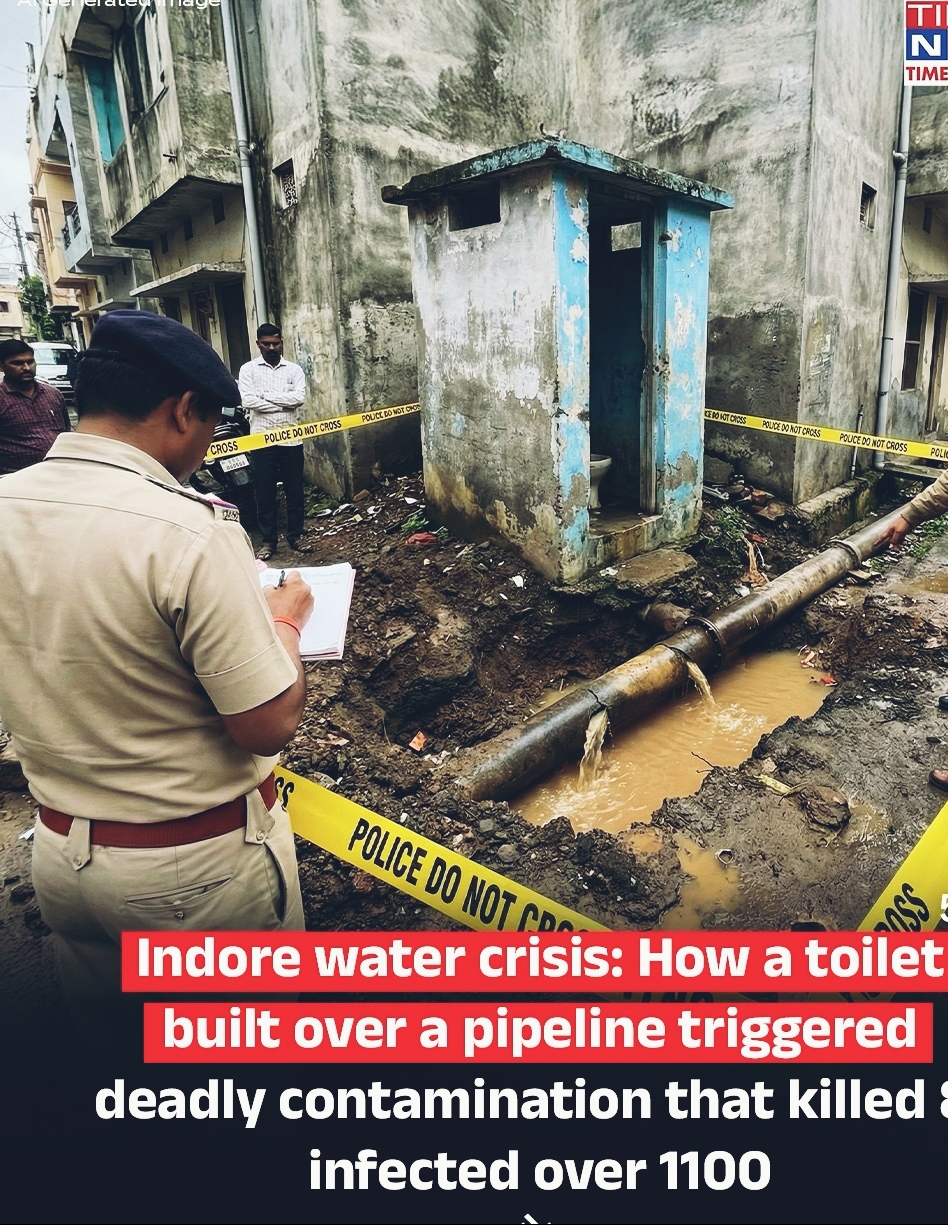

The anatomy of the disaster reads like a textbook on institutional failure. Sewage infiltrated the drinking water network through a ruptured pipeline running beneath an illegally constructed toilet and an unauthorised structure near a police outpost—an almost symbolic convergence of neglect. Urban planning failed to regulate land use, construction oversight failed to detect violations, sanitation enforcement failed to prevent illegal connections, and pipeline maintenance failed to protect the most critical public utility. This was not an unpredictable accident; it was layered negligence turning lethal. Laboratory tests later confirmed multiple bacterial pathogens. Predictably, the outbreak hit children and the elderly hardest, reaffirming a brutal rule of governance failures: vulnerability is always the first casualty. Clean pavements and star ratings could not neutralise poisoned taps.

What deepened the crisis was epistemic confusion—uncertainty about truth itself. Official death figures shifted uneasily from eight to ten to thirteen, while local accounts suggested higher numbers. In moments of trauma, numbers are not just data; they are moral signals. The inability to communicate with precision shattered public trust when it was most needed. Even as authorities acknowledged that over 160 patients were undergoing treatment, the city appeared administratively disoriented. A municipality capable of tracking every kilogram of segregated waste suddenly lost clarity over its dead. This contradiction exposed the dangers of governance driven by visibility rather than resilience. Sanitation had become performative success; water safety, invisible and unphotogenic, had been left to decay beneath the surface.

Administratively, the response after the outbreak was swift and serious. Contaminated supply lines were sealed, officials suspended, emergency repairs sanctioned, and a high-level probe initiated. Citywide random water sampling was ordered to prevent further outbreaks. The local MLA and cabinet minister, remained on the ground, coordinated relief, acknowledged failures, and announced free medical treatment up to ₹50,000 per affected family in private hospitals—an intervention that undoubtedly prevented financial devastation for many. Yet no efficiency of response can morally compensate for years of neglect. Governance is not judged only by how it reacts to tragedy, but by whether it prevents tragedy from becoming possible in the first place.

The episode escalated from administrative failure to political rupture on New Year’s Eve. During a late-night interaction, a journalist pressed the minister on accountability beyond immediate relief—on systemic responsibility and leadership failure. Exhausted and visibly irritated, he dismissed the question with a slang Hindi term implying “nonsense” and walked away. One word was enough. It went viral instantly. Opposition leaders weaponised it as proof of arrogance and insensitivity, demanding resignation. A subsequent clarification on X cited exhaustion after two days of nonstop crisis management. But politics, like water, follows gravity. Once a narrative settles, explanations rarely disinfect it. That single word came to embody a deeper rage: citizens were not only mourning deaths, they were confronting the feeling of being trivialised by power.

Indore’s tragedy is not an anomaly; it is a warning written in contaminated water. Across Indian cities, drinking water and sewage pipelines run side by side, aging invisibly while civic pride is measured in rankings, festivals, and branding exercises. Contemporary governance increasingly rewards what can be photographed, tweeted, and awarded—not what must be excavated, audited, and monotonously maintained. Real governance lives underground: in pipelines, sensors, inter-departmental coordination, and preventive maintenance budgets that never win applause. Indore mastered cleanliness as spectacle but neglected water security as infrastructure. The lesson is unforgivingly simple: you cannot drink awards, and you cannot purify negligence with trophies. Until Indian cities value invisible systems as much as visible success, even the cleanest among them will remain just one leak away from their dirtiest truths.

Visit arjasrikanth.in for more insights

One response to “Eight Trophies, Thirteen Coffins: India’s Cleanest City Drank from Its Own Sewer”

Is it right to say Indore has only ornamental value similar to a gold plated ornament

LikeLike