Verdicts, Vengeance, and the Vanishing of Democracy: South Asia’s Never-Ending Political Thriller

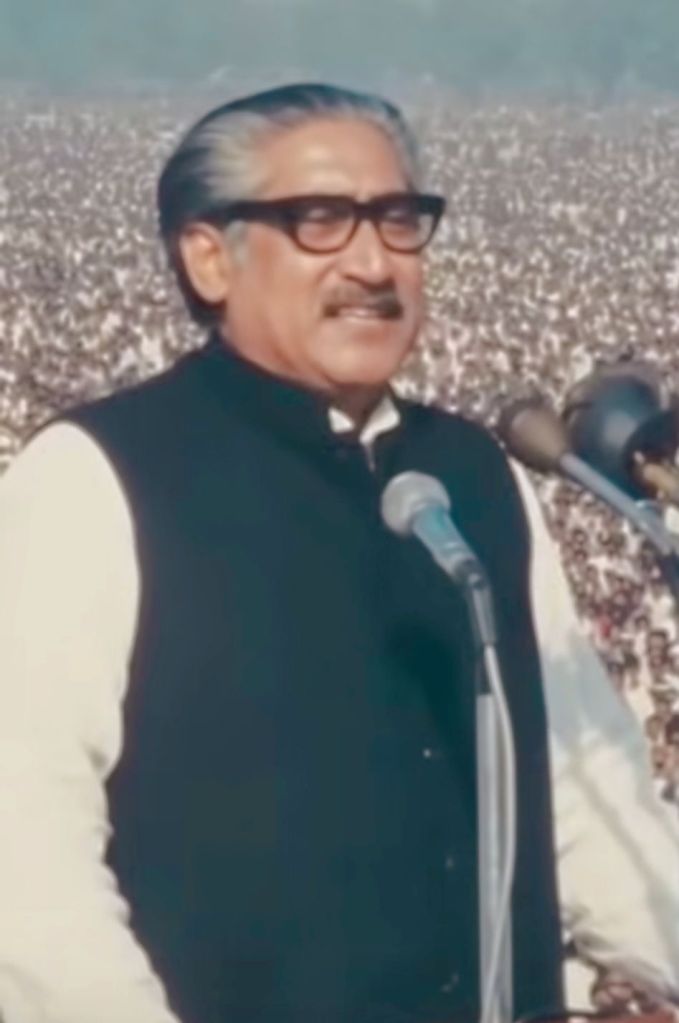

South Asia has once again been dragged back to its most familiar—and most frightening—political script. The death sentence handed to former Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has not merely ignited debate; it has reopened the region’s deepest psychological vaults.

Convicted of crimes against humanity linked to the 2024 uprising, tried in India, and now entangled in a cross-border diplomatic storm, Hasina’s fate sits at the intersection of political loyalty, national trauma, and geopolitical fault lines. For many Bangladeshis, the verdict signals long-delayed accountability; for others, it is a chilling replay of a political culture where justice is inseparable from power. For India, her extradition request poses one of the most challenging diplomatic decisions in recent years.

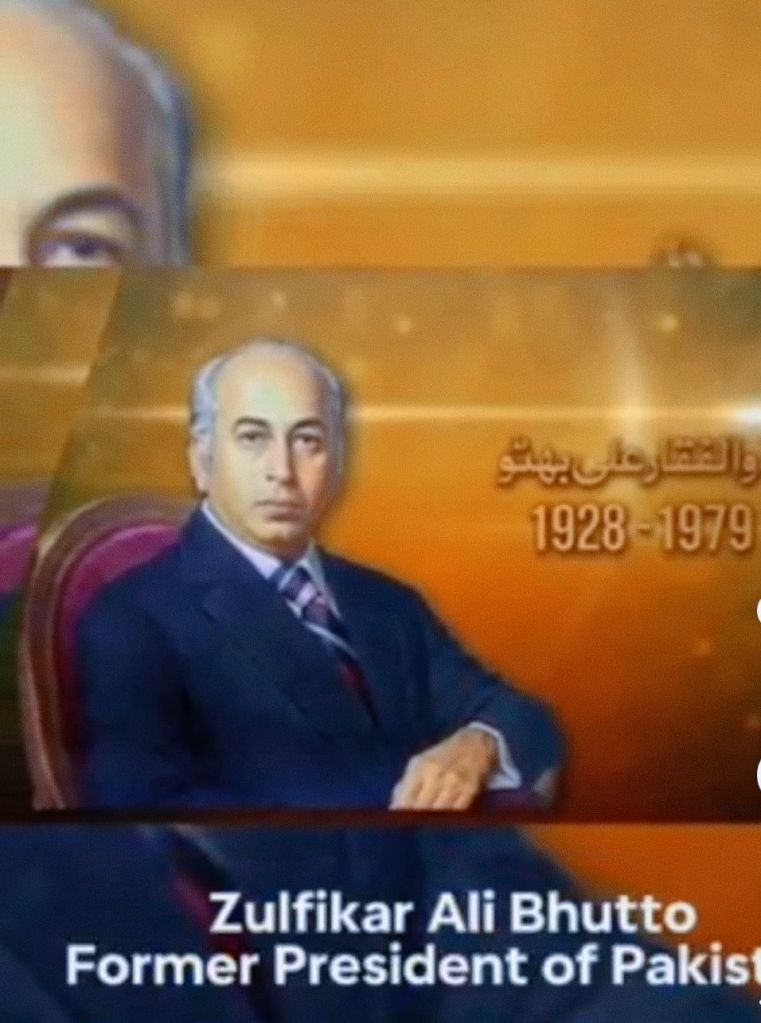

South Asia’s political history has never followed a peaceful arc. It is written not in ballots but in bullets, coups, trials, and untimely deaths. Pakistan and Bangladesh, in particular, resemble a political thriller that no citizen wishes to endure but cannot escape. The assassination of Pakistan’s first Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan in 1951 set a precedent that leadership in the region is rarely relinquished voluntarily. Power is seized, sabotaged, or eliminated. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s downfall in 1979—through a military coup followed by a judicial execution—remains one of the starkest examples of how legality can be weaponised. His daughter, Benazir Bhutto, was later assassinated in 2007, reinforcing Pakistan’s position as a polity where political violence is not episodic—it is structural.

Bangladesh’s political legacy runs parallel but carries its own tragic intensity. The 1975 assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the nation’s founding father, along with most of his family, shattered the country’s moral centre. Countercoups, ideological wars, and political vendettas defined the decades that followed. President Ziaur Rahman’s assassination in 1981 further entrenched the belief that power in Bangladesh is a battlefield, not a constitutional office. Even as democracy returned in the 1990s, the retributive culture deepened. The International Crimes Tribunal, while seen by many as a long-overdue correction of 1971’s horrors, became a lightning rod of partisanship. Executions of opposition leaders strengthened perceptions that justice was selective and political in intent.

Against this backdrop, Sheikh Hasina’s death sentence becomes another chapter in a narrative defined more by revenge than reconciliation. As the daughter of an assassinated leader and the country’s longest-serving Prime Minister, her political journey is inseparable from Bangladesh’s collective trauma. For her supporters, the verdict reflects political targeting. For her critics, it is a long-delayed reckoning. For the region, it is a flashing red signal of institutions once again bending under the weight of politics.

Why do these cycles persist? Because South Asian politics is existential, not ideological. Institutions remain fragile; personalities dominate; and power transitions are treated as life-or-death contests. In Pakistan, the military has entrenched itself as the final arbiter. In Bangladesh, the Awami League–BNP rivalry has hollowed out trust in electoral and judicial processes. Courts become stages for political combat, not impartial adjudication. Losing power is perceived not as a temporary democratic verdict, but as annihilation. As long as these structural distortions remain, the region remains hostage to its past.

But alternatives exist. Other nations once trapped in similar cycles have rebuilt themselves through institutional reform, public accountability, and political courage. Germany fortified its democracy through strict constitutionalism. South Africa used truth-telling, not vengeance, to rebuild fractured society. Countries like Colombia and Northern Ireland showed that even long-standing internal conflicts can be softened through dialogue and restorative frameworks. Pakistan and Bangladesh can follow similar paths—but only if they stop recycling old hostilities and start rewriting the rules.

South Asia’s future demands leaders who exit office, not the world, when times change; verdicts that heal, not harden divisions; institutions that outlast personalities; and political cultures where losing an election does not mean losing existence. For Bangladesh, how the Hasina verdict is handled will determine whether it becomes a step toward accountability or another scar in a long line of political tragedies. For India, the extradition dilemma will test both principle and partnership.

The next generation of South Asians deserves a politics where headlines celebrate progress, not death sentences; where hope outshouts hysteria; where democracy is not theatre but trust. Breaking the cycle will be painful—but perpetual instability is far costlier. South Asia cannot afford another chapter of blood-soaked politics. It deserves a new narrative—one written not with vengeance, but with vision.

Visit arjasrikanth.in for more insights