From cultural vibrance to civic strain, India’s booming religiosity is redefining coexistence.

India has always lived its religion in full view of the world. The fragrance of morning incense drifting across neighbourhoods, the azaan rising over rooftops, and bhajans echoing through public parks have long defined a civilisation that instinctively blends the sacred with the social. Yet, over the past decade, public religiosity has undergone a marked escalation. Navratri dances erupting in airport terminals, Sikh Guru Jayanti processions bringing major avenues to a halt, azaans broadcast on competing loudspeakers, and all-night jagrans vibrating through densely packed colonies reflect a new cultural moment—one where private devotion increasingly manifests as high-volume assertion. Beneath this amplified soundscape lies not only contestation but also a profound human impulse: the need of communities to express identity, maintain continuity, and seek belonging in a rapidly shifting society.

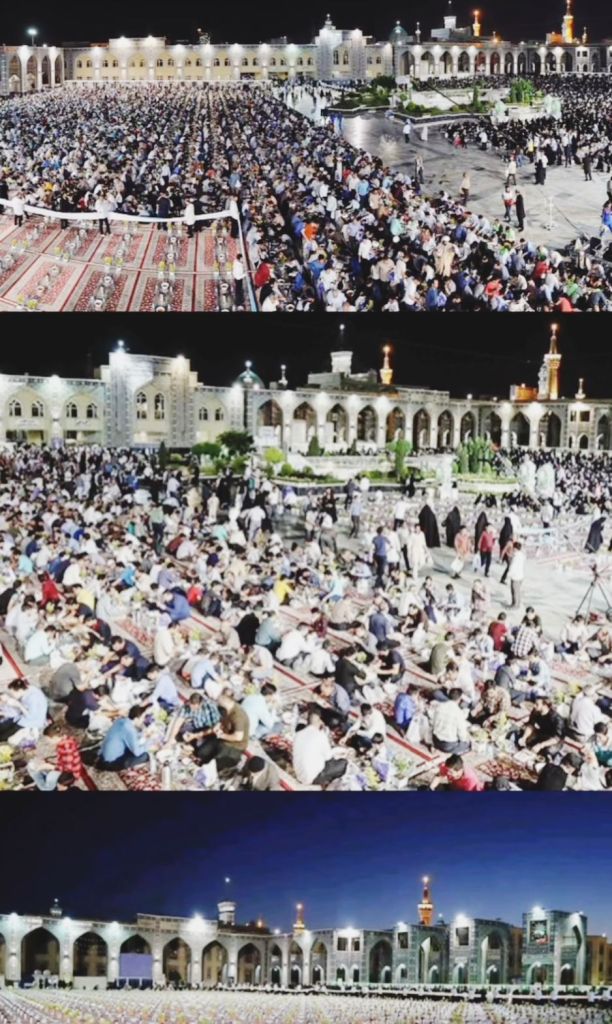

Public celebration of faith is not new to India, but the scale, frequency, and technological intensity of these expressions have changed significantly. Hindu festivals—from Navratri to Diwali—have expanded into citywide spectacles powered by elaborate lighting, large stages, and high-decibel sound systems. The proliferation of visual symbols such as the “angry Hanuman” decal signals a shift from inward devotion to outward identity expression. Muslim religious practice has also adapted: many mosques now conduct multiple Friday congregations post-COVID to manage crowds more efficiently—a pragmatic reform that has become routine. In culturally refined Kolkata, neighbourhoods like Raja Bazar and Circus Avenue turn into continuous sound chambers during festivals. These changes reflect not merely heightened piety but broader structural forces—urban density, rising mobility, political dynamics, and evolving economic aspirations.

However, when religious expression flows unchecked into civic spaces, predictable tensions emerge. Emergency services in Delhi routinely face delays as processions immobilise arterial roads. Noise levels frequently surpass statutory limits, disturbing sleep patterns and harming vulnerable groups such as children, the elderly, and patients recovering at home. The environmental fallout—from cracker-driven pollution spikes during Diwali to waste generated by large gatherings—erodes public health. The clash of loudspeakers from temples and mosques creates an acoustic competition that neither tradition nor law endorses. These challenges are not indictments of faith but of inadequate civic management and diminishing social empathy. Authentic devotion enriches society; it does not suffocate it.

India’s constitutional framework provides a nuanced guide for navigating these complexities. The right to freely profess, practise, and propagate one’s religion is fundamental, but it is not absolute. It is circumscribed by public order, health, morality, and the rights of others. Judicial interpretation has repeatedly differentiated essential practices from non-essential ones. Loudspeakers, for example, are not intrinsic to any faith tradition, even if they have historically served functional purposes. In an era where every individual has access to personal alarms, clocks, and mobile reminders, the functional necessity for public sound amplification stands significantly reduced. What remains essential is mutual respect—a civic duty as much as a moral obligation in a pluralistic society.

Yet, the landscape is not without hope. Across India, communities are embracing innovation and self-regulation. Festival committees increasingly adopt eco-friendly practices such as clay idols, symbolic immersions, and low-noise celebrations. “Green Diwali” campaigns have gained remarkable traction. Interfaith dialogues and citizen-led agreements on procession timings and routes have reduced conflict in several cities. These bottom-up efforts demonstrate that coexistence cannot be mandated solely by law; it must emerge from collective negotiation and responsible citizenship. India’s spiritual adaptability—its ability to modernise rituals without eroding their essence—remains one of its greatest civilisational strengths.

The task ahead is to strike a balance between vibrant public faith and functional civic life. Cities must establish designated celebration zones, deploy technology-enabled sound monitoring, and enforce regulations uniformly across communities. Religious organisations must cultivate sensitivity to shared urban spaces. Individuals, too, have a pivotal role—pausing processions to let an ambulance pass, moderating volume levels, or ensuring festivities do not infringe upon another’s peace. India’s public religiosity is not disappearing, nor should it. But as urban spaces grow tighter and lives more interconnected, the aspiration must be to celebrate responsibly rather than loudly.

Ultimately, the real test of faith lies not in how dramatically it occupies public space but in how thoughtfully it accommodates others. India’s unique genius has always been its ability to harmonise the expansive with the intimate—to transform a neighbourhood lane into a festival ground while remembering that it is, above all, a shared civic space. If we achieve this equilibrium, we will not merely manage the rise of public religiosity; we will transform it into a global model of pluralistic coexistence.

Visit arjasrikanth.in for more insights