As the Election Commission embarks on a nationwide overhaul of voter rolls, the line between cleansing democracy and corrupting it has never been thinner — and the fate of India’s elections may rest on a few lines of code.

In the bustling theatre of the world’s largest democracy, where nearly a billion citizens prepare to vote, a silent revolution is unfolding — not in rallies or debates, but in databases. The Election Commission of India’s Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls is being hailed as one of the most ambitious administrative exercises in decades — a mission to scrub clean the foundation stone of democracy: the voter list.

The logic is simple yet profound — one citizen, one vote. Nothing less, nothing more. But as the nation embarks on this mammoth digital purge, questions emerge: Can democracy survive a data war? And can technology, once meant to protect elections, become their most dangerous foe?

At its heart, the SIR is democracy’s version of spring cleaning — removing the dead, deleting duplicates, and adding new, first-time voters to the rolls. With 950 million registered voters and millions turning 18 each year, such periodic revisions are essential. Migration, deaths, and clerical errors leave the lists swollen and unreliable. This time, however, the Commission isn’t merely tidying up — it’s pressing reset.

Across Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, Kerala, Assam, and other states, voters are being asked to re-verify their details, re-submit forms, and re-establish their presence in the electoral system. For every polling booth with 1,200 voters, this means thousands of verifications — an administrative marathon powered by data entry, field work, and digital audits.

But even as one arm of the state toils to protect the sanctity of the rolls, another front is opening in the shadows — one that threatens to undo the very credibility the SIR seeks to build.

Earlier this year, Karnataka’s Special Investigation Team (SIT) uncovered a chilling case of digital election fraud. Using just a few mobile numbers and ₹5 worth of OTPs, hackers generated fake logins, filed Form-7 deletion requests, and erased over 6,000 legitimate voters from a single constituency. One-time passwords, once the symbol of security, became tools of theft. In a constituency decided by a 698-vote margin, democracy itself hung by a digital thread.

The probe traced the network to political operatives, even reaching Dubai. The revelation was stark: the age of booth-capturing and ballot-stuffing had given way to server-capturing and database manipulation.

This is the paradox of India’s digital democracy. The same technology that enables transparency also invites tampering. Every innovation comes with a new vulnerability. Every firewall creates a smarter hacker.

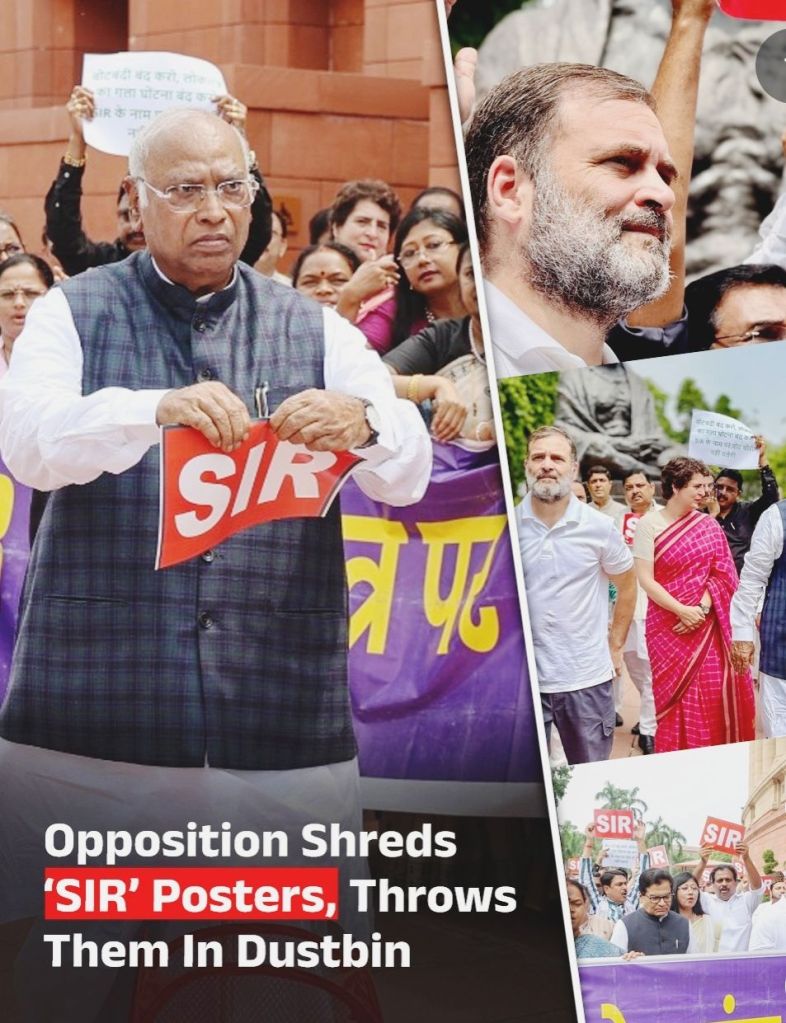

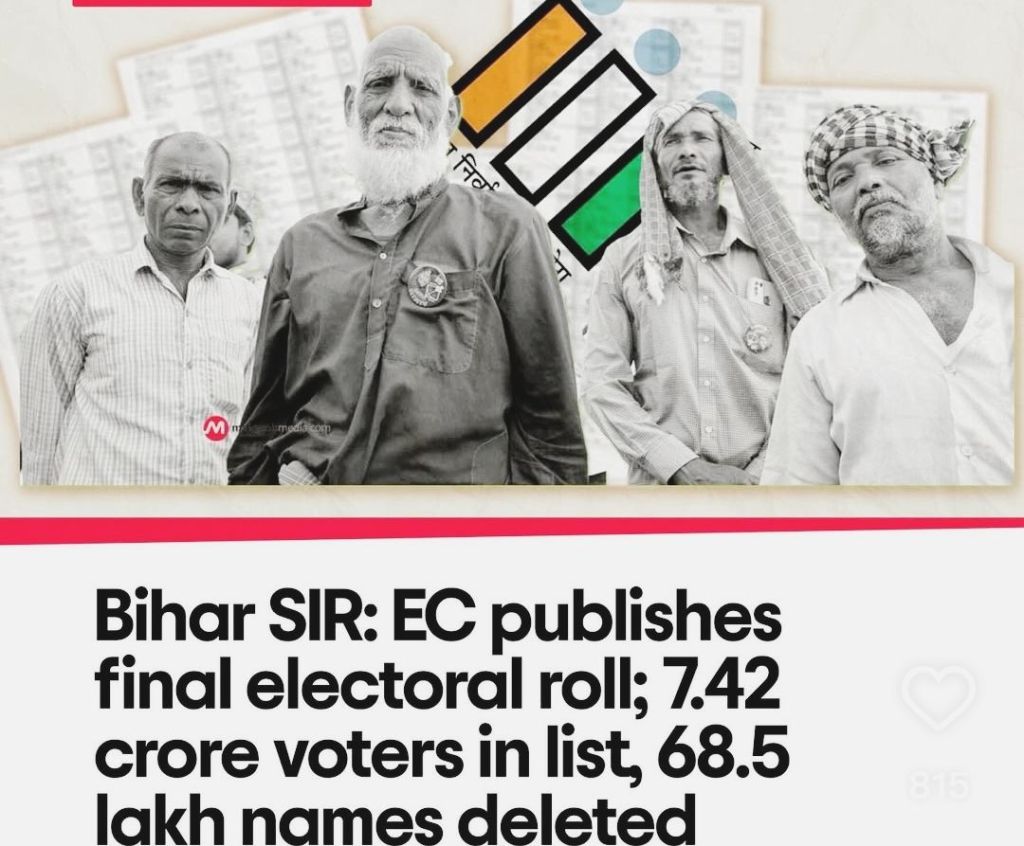

That’s why the SIR is not merely an administrative challenge; it is a test of trust. In a country where perception is often stronger than proof, even a minor error in deletion or addition can ignite political chaos. Bihar’s recent verification drive, which saw 65 lakh names dropped, triggered a storm of accusations and counterclaims. Opposition leaders cried foul, alleging “systematic deletion” of valid voters — a charge the ECI denies. But perception, once poisoned, is hard to purify.

Every missing name on a voter list is not just a statistic; it is a silenced voice. And in a democracy, silence is the most dangerous noise of all.

As India gears up for the 2025 Bihar Assembly elections and beyond, the SIR carries both promise and peril. It could either strengthen democracy’s backbone or fracture its faith.

Adding to the drama is India’s dynastic political landscape. While the Election Commission attempts to cleanse the voter lists, the political class recycles surnames — sons, daughters, and grandsons of former chief ministers returning to the ballot. In a nation where democracy was meant to be meritocratic, politics risks becoming hereditary. The contrast couldn’t be sharper: bureaucrats fight to purify the process, while politicians preserve the pedigree.

The future, therefore, hinges not just on data hygiene but data integrity. The Election Commission must go beyond the rhetoric of reform. It must build digital firewalls, enforce multi-factor authentication, and create public verification dashboards where citizens can instantly check their voter status. Cybersecurity experts should sit alongside electoral officers; technology must be audited like ballots.

And equally important — the Booth Level Officers (BLOs), the foot soldiers of Indian democracy, must be empowered with digital literacy to detect and report anomalies. They are the human bridge between the algorithm and the electorate.

Because in the end, no technology can replace trust — and no democracy can survive without it.

The success of this grand clean-up will not be measured in the number of deletions or new registrations, but in the confidence of citizens that their right to vote is secure, untampered, and sacred. If handled transparently, the SIR could become a global model for balancing digitization with democratic ethics. But if it falters, it could fuel alienation, distrust, and digital disenfranchisement.

In an age when deepfakes shape truth, bots shape opinion, and algorithms influence elections, the battle for democracy is no longer fought in polling booths — it’s fought in databases, codes, and servers.

India stands today at that razor’s edge — between digital empowerment and digital enslavement. The ghosts of data manipulation whisper warnings, but the shadows of democracy still hold light.

And as the Election Commission embarks on this colossal exercise, one message must resonate from Delhi’s corridors to the smallest polling booth: the voter list is not just a document — it is democracy’s DNA. Protect it, or risk rewriting the future.

Visit arjasrikanth.in for more insights