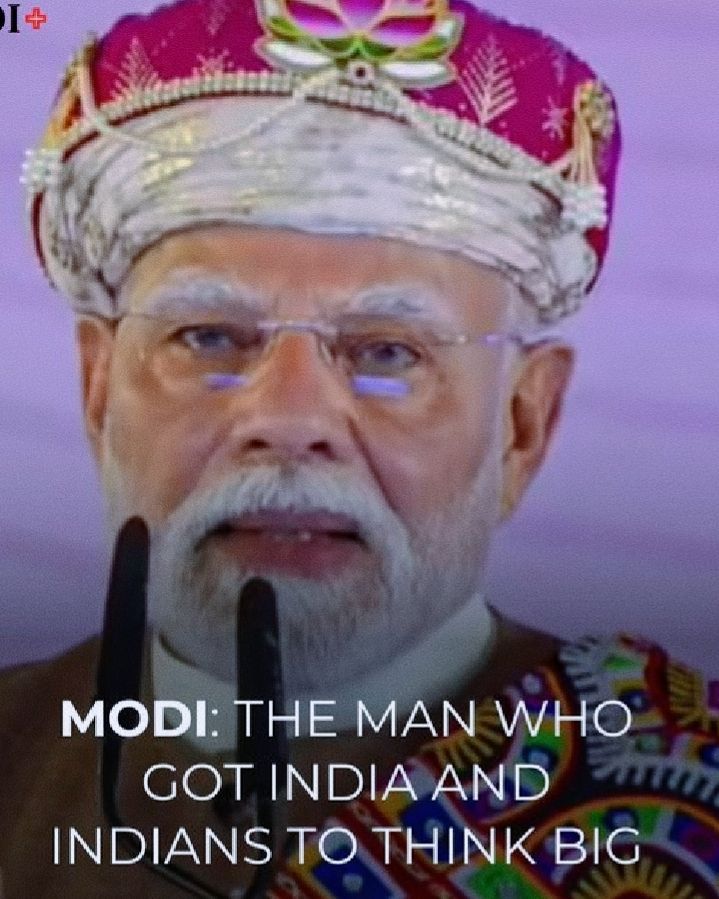

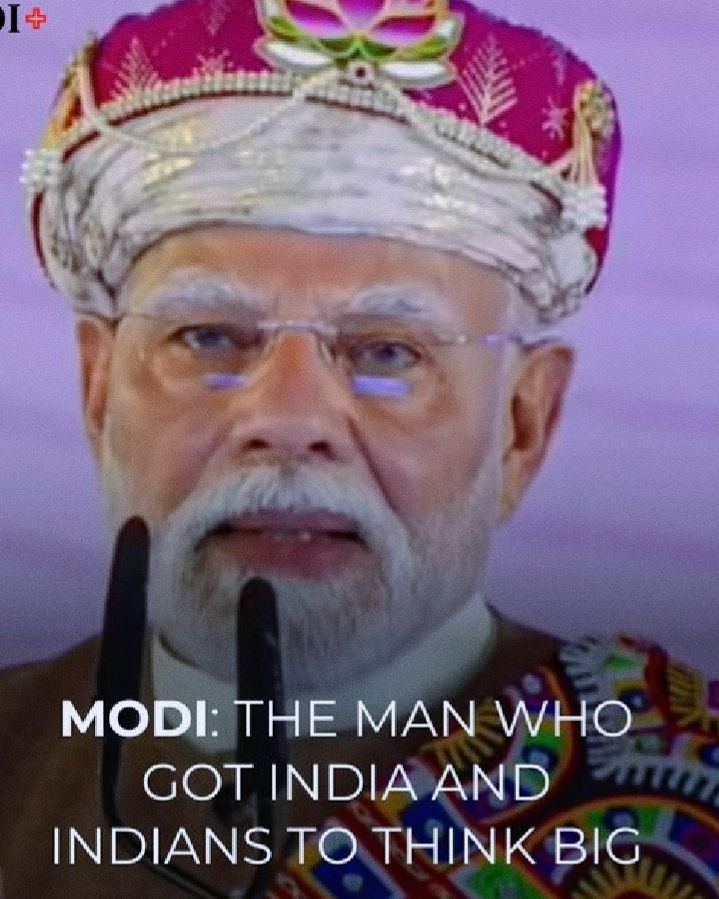

One leader turned welfare into ideology, caste into coalition, faith into reference, and power into permanence in 21st-century India

When history eventually writes the chapter on India’s early 21st-century politics, one name will loom disproportionately large—Narendra Modi. Admired, criticized, or debated, there is no denying that he has transformed India’s political landscape in ways few leaders since Independence have managed. His impact has not been about flashes of charisma alone, but about a layered and systematic reworking of India’s political culture. In eleven years, Modi has made Indian politics look, sound, and function differently, and that legacy is both undeniable and far-reaching.

The first tectonic shift has been institutional. For decades, the Congress Party was the default party of governance. Today, that monopoly has crumbled. Under Modi, the BJP has not only replaced Congress at the national level but has spread into regions once considered off-limits—from Bengal to the Northeast, from Telangana to even the peripheries of Kerala. Politics is no longer a competition between equals; it is now BJP versus everyone else. This dominance is unlikely to be temporary, as it reflects a deep organic spread.

A second transformation lies in the party’s social base. The BJP was once caricatured as an “upper caste Bania party.” Modi, himself an OBC, decisively broadened this appeal, drawing in non-dominant castes, Dalits, and poorer communities. Today, barring minorities, the BJP’s support base cuts across caste lines, redefining identity politics in India. By doing so, Modi permanently rewrote the grammar of caste equations, creating a new axis of electoral arithmetic.

Equally important has been the centrality of the Hindu question. Under Modi, politics has acquired a Hindu axis that no party can ignore. Even critics of the BJP are compelled to assert they are “not anti-Hindu.” From Ayodhya to Sabarimala, temple visits to symbolic rituals, religion has become an inescapable reference point. Modi did not conjure this sentiment from thin air, but he mainstreamed it until it became the default frame of national politics.

Foreign policy, too, has been repurposed as a tool of domestic legitimacy. Where earlier leaders treated international engagement as a separate sphere, Modi blurred the lines. Diaspora rallies in New York or Sydney have been crafted as spectacles as much for Indian voters at home as for audiences abroad. This blending has not been flawless—at times, like Trump’s mediation remark, it sparked awkward defensiveness—but overall, Modi succeeded in giving Indians a sense of global visibility and pride like never before.

On welfare, Modi rewrote the political playbook. Direct benefit transfers, free food grain for 80 crore citizens, health schemes, toilets, and gas connections have reshaped welfare into the centrepiece of governance. Critics label this populism, but its scale is unparalleled. Every state party, from Mamata Banerjee’s Trinamool to the Aam Aadmi Party in Delhi, has been forced to adopt similar models. Welfare is no longer supplementary; it has become the main course of political legitimacy.

Inside the BJP, the transformation has been equally striking. Once a “party with a difference,” it now mirrors the centralized high-command model of the Indira Gandhi Congress era. Modi and Amit Shah hold the reins, and state leaders toe the line. This centralization has enhanced discipline but diluted ideological purity, with defectors from rival parties now embraced. Yet electorally, this formula has delivered landslides.

Polarization is another defining marker. The cooperative spirit of earlier eras, when Vajpayee would lead delegations abroad on behalf of Congress governments, feels like a relic. Today, consensus is scarce, and partisanship runs deep. While some lament this erosion of trust, it reflects the ruthless competition of modern politics.

Meanwhile, the RSS has stepped out of the shadows. Once dismissed as a cultural outlier, it is now firmly at the core of India’s politics. Its gatherings make headlines, its influence shapes policy, and its Delhi presence marks a new phase in its journey from the margins to the mainstream.

Economically, the record is mixed but steady. Growth has averaged around 6–6.5% despite global turbulence and the pandemic. Fiscal discipline has been maintained, inflation kept under relative control, and privatization in defence has opened new sectors. Yet critics point to abandoned farm and labour reforms, and to the squeeze on the middle class through GST and fuel taxes while corporates enjoy tax cuts. Stability, though, has been Modi’s hallmark in a volatile global environment.

Perhaps the most underappreciated achievement is succession planning. Beyond Modi and Shah, a new generation of leaders—Yogi Adityanath, Himanta Biswa Sarma, Devendra Fadnavis—has emerged. Unlike dynastic parties, the BJP under Modi has institutionalized ambition, ensuring continuity beyond his own tenure.

India under Modi is not flawless. It is more polarized, more centralized, and less tolerant of dissent. Yet politics is about power, and power is about staying relevant. Modi has taken identity, welfare, foreign policy, and party organization and stitched them into a new political mosaic. The pieces may not please everyone, but they fit together into a design unmistakably his own. For better or worse, Narendra Modi has changed Indian politics so thoroughly that the old order now feels like a faded photograph.

Visit arjasrikanth.in for more insights