The Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025 turned centuries-old charity into the country’s most contested real estate saga, forcing the Supreme Court to walk the tightrope between belief and governance.

India has always been a stage where the sacred and the secular wrestle for space, and the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025 has now become the centrepiece of that struggle. With more than eight lakh registered properties spread over nearly nine and a half lakh acres, waqf lands are not just repositories of religious endowment but also some of the most hotly contested real estate holdings in the country. Their importance is immense, both in heritage and in material value, and it is precisely this unique intersection of faith and property that landed before the Supreme Court’s bench this September.

The institution of charitable endowments in Islamic tradition represents one of the oldest systems of continuing philanthropy. Based on the principle that once a property—whether land, building, cash, or even movable assets—is donated for a religious or charitable purpose, it becomes irrevocable, waqf embodies the ideal of “flowing charity.” The donor surrenders all rights, and the asset is meant to serve the designated cause perpetually. The belief is that while worldly possessions perish, certain acts such as continuous charity, knowledge imparted, and prayers offered by one’s children endure beyond death and sustain the soul.

This tradition dates back to the earliest periods of Islamic civilization, passed through rulers and dynasties before becoming embedded in Indian society during medieval times. As properties multiplied, regulation became necessary. Colonial India saw the Religious Endowments Act of 1863 and the Charitable Properties Act of 1890, followed by legislation in 1913 and the Sharia Act of 1937. After Independence, the Waqf Act of 1954 established a modern framework, later revised in 1995 and amended again in 2013. Each layer of law gave boards more authority, but also invited more criticism.

The 1995 Act proved especially transformative. It empowered waqf boards to declare assets as waqf, leaving private claimants with little recourse beyond specialized tribunals. These tribunals often became the final word, since writ jurisdiction in High Courts was limited. To make matters more lopsided, boards could assert ownership at any time, while private challengers faced strict limitation periods. The 2013 amendments further tightened the boards’ grip, causing concerns that unchecked powers were breeding injustice.

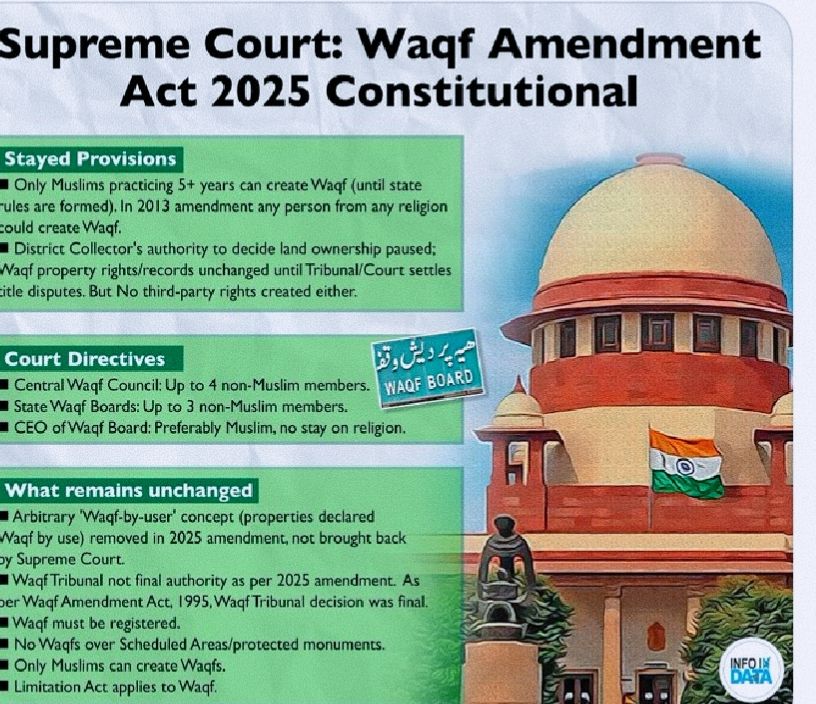

When Parliament pushed through the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, controversy exploded. Critics feared it would hand sweeping, arbitrary powers to officials and undermine community autonomy. The Supreme Court’s interim ruling this September did not strike with a hammer but rather sliced with a scalpel. Certain provisions were frozen—most notably the clause allowing district collectors to decide property ownership, a move that would have handed enormous discretion to revenue officers. The requirement that an individual prove at least five years of religious practice before creating a waqf was also struck down, with the Court declaring that religiosity cannot be measured by bureaucratic yardsticks.

The Court also trimmed the expanded membership structure of waqf councils, which had diluted self-representation in favour of non-community members. It restored balance while leaving space for inclusivity. Importantly, the contentious principle of “waqf by user”—which allowed informal or customary use to evolve into a formal claim—was deleted for the future, though registrations prior to April 2025 remain untouched. These surgical interventions reflected the Court’s philosophy that parliamentary laws are presumed constitutional and must not be dismantled wholesale except in rare circumstances. Instead, the Court allowed the Act to stand but pared away its sharpest edges, leaving the final verdict for a later stage.

For observers, the judgment was a tightrope walk. Supporters hailed it as a democratic safeguard, protecting against potential misuse while retaining Parliament’s prerogative. Critics, however, saw it as incomplete, arguing that several problematic provisions still survive and could be weaponized against vulnerable communities.

The sheer scale of the challenge underlines why reforms are urgent. More than 40,000 tribunal cases involving waqf land remain pending, many of them bitter disputes within the community itself. Allegations of arbitrary additions to waqf records have deepened mistrust, and thousands of acres lie frozen in litigation. Without systemic change, this vast endowment risks collapsing under its own weight. Yet reforms imposed without consultation threaten to erode trust and provoke unrest.

The way forward demands recalibration, not confrontation. Digitization of records, geotagging of properties, and open public access could usher in unprecedented transparency. Strengthening tribunals with more judges, tighter timelines, and greater independence would reduce the crushing backlog. Training officials, both in revenue and waqf administration, would minimize friction and prevent arbitrary decisions. Above all, structured dialogue between state authorities and community leaders must be institutionalized so that reforms are driven by trust rather than suspicion.

The Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025 is more than a technical statute. It is a mirror reflecting India’s ongoing struggle to reconcile governance with belief. The Supreme Court’s cautious pruning shows that the gavel cannot silence the prayer, and the prayer cannot deny the gavel. The ultimate verdict will not be found merely in legal text but in whether transparency, fairness, and faith can coexist on the same soil. Only then will India’s sacred acres cease to be battlefields and instead become bridges between heritage and modernity.

Visit arjasrikanth.in for more insights