South Asia’s uprisings topple dynasties while India’s noisy democracy bends, absorbs, and endures.

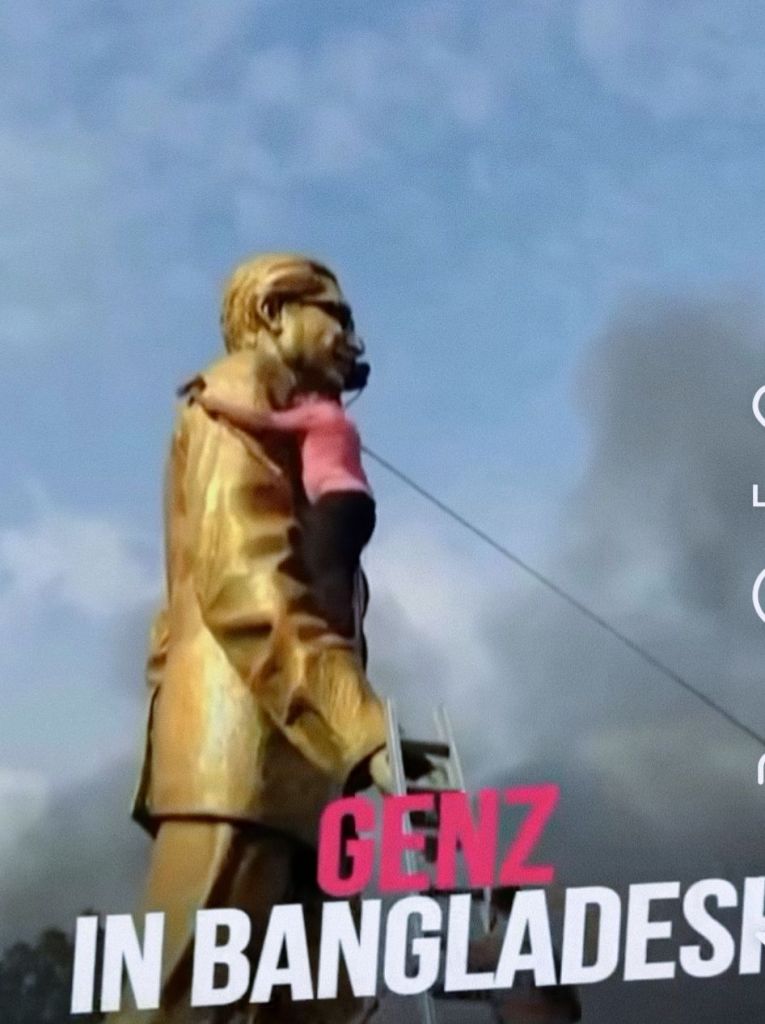

The subcontinent has always been a theatre of turbulence, where governments can be shaken in a matter of days. In July 2022, Sri Lanka’s presidential palace was stormed by furious citizens, forcing Gotabaya Rajapaksa to flee under the cover of night. In August 2024, Dhaka’s streets erupted, Sheikh Hasina bowed out after days of relentless unrest, and a Nobel laureate was summoned to lead an interim administration.

Kathmandu has danced on the edge of chaos more times than its mountains have seen avalanches, with revolutionary leaders proving more adept at guerrilla slogans than building durable institutions. Even Pakistan staged its own moment of frenzy on May 9, 2023, when Imran Khan’s supporters torched monuments, barged into cantonments, and screamed of revolution—only for the tide to fizzle, leaving Khan in jail and the old guard intact.

The pattern is obvious: youth-led outrage, turbocharged by social media, spilling into the streets, paralyzing institutions, and shoving governments to the brink or beyond. The contagious nature of digital uprisings has redrawn political maps from Colombo to Kathmandu. Yet to assume that such sparks could set New Delhi aflame in the same way betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of India’s democracy. For all its flaws, noise, and imperfections, India is not a brittle state; it is a resilient one. Its fabric—constitutional, federal, and institutional—absorbs tremors that would break weaker polities.

Take Sri Lanka. Its collapse was the story of an economy eating itself alive: foreign reserves evaporated, fuel lines snaked for miles, fertilizers were banned in a fit of ecological adventurism, and the Rajapaksa dynasty drained public trust. The state itself hollowed out, leaving only the army as the last pillar of credibility. When the streets surged, there was nothing left to hold. Nepal is another tale: revolutionary politics without institution-building. A country that replaced monarchy with democracy but never grew roots deep enough to endure crisis. Governments flipped like coins, and when the youth turned against the political class, there were no buffers. Bangladesh? Its brittle edifice was built on authoritarian consolidation, opposition boycotts, and a job quota system that privileged lineage over merit. When anger exploded, institutions folded like cheap umbrellas in a storm.

India, by contrast, bends but does not break. Functionality is the operative word. A government may stumble, even falter, but as long as its Parliament sits, its judiciary rules, its Election Commission conducts polls, its civil services grind on, and its federal system disperses power, the state endures. The Indian state does not collapse under slogans or hashtags; it absorbs them, sometimes even co-opts them, and channels them back into electoral politics. That is why even in moments of grave unrest—be it Jayaprakash Narayan’s Total Revolution in the 1970s or Anna Hazare’s anti-corruption crusade a decade ago—the government of the day did not crumble in the streets. Indira Gandhi was defeated in 1977 not by mobs but by ballots. The UPA fell in 2014 not by fast-unto-death but by votes.

Three ingredients explain this resilience. First, India’s security apparatus is trained not to unleash massacre but to manage dissent. The CRPF, state police, and paramilitary forces know crowd control, not just crackdown. Second, India provides space for anger. A noisy opposition, quarrelsome legislatures, endless television debates, and regional satraps with their own fiefdoms ensure that citizens never feel locked out of the system. Third, federalism acts as a release valve. Power does not sit monolithic in Delhi. It is scattered across Chennai, Kolkata, Patna, Lucknow, and dozens of other capitals. Governments rise and fall at the state level regularly, reassuring citizens that change is possible without burning the edifice.

This contrasts starkly with fragile neighbours. Nepal’s guerrillas never learned negotiation. Sri Lanka’s dynasts consumed trust like termites. Bangladesh’s rulers treated opposition as enemies, not partners. Their states were brittle; India’s is supple. That difference is why angry young people in India, however energized by hashtags, ultimately turn to campaigning, voting, and debating rather than to storming Rashtrapati Bhavan.

But let there be no illusion. India’s democracy survives not by default but by constant renewal. Parliament must remain a place for debate, not merely partisan theatrics. Courts must guard liberties without hesitation. Federalism must be respected in spirit, not just on paper. Opposition parties must be recognized as indispensable, not delegitimized. These are not luxuries; they are safety valves. Without them, discontent could harden into something uglier.

The real lesson of South Asia’s recent uprisings is that street fury is fleeting unless married to organized politics. Pakistan’s May 9 fizzled because it lacked institutional spine. Sri Lanka’s Aragalaya shook a dynasty but did not rebuild the economy. Bangladesh’s youth won a resignation but inherited instability. Revolutions without institutional anchoring collapse into chaos. In India, the script is different. Protests may rattle governments, but institutions cushion the blow, and the ballot box decides the final act.

India is loud, argumentative, chaotic, and often infuriating. Yet this very chaos is its strength. Where brittle states snap, India stretches. Where neighbours collapse, India absorbs. Hashtags here can trend, streets can roar, but when the dust settles, the final verdict is written not on placards but on ballot papers. That is why the subcontinent’s contagion of collapses will stop at India’s borders.

Because in India, revolutions do not storm palaces. They queue up at polling booths.

Visit arjasrikanth.in for more insights