Cleanliness Becomes a Cage and Sacrifice Becomes a Sickness

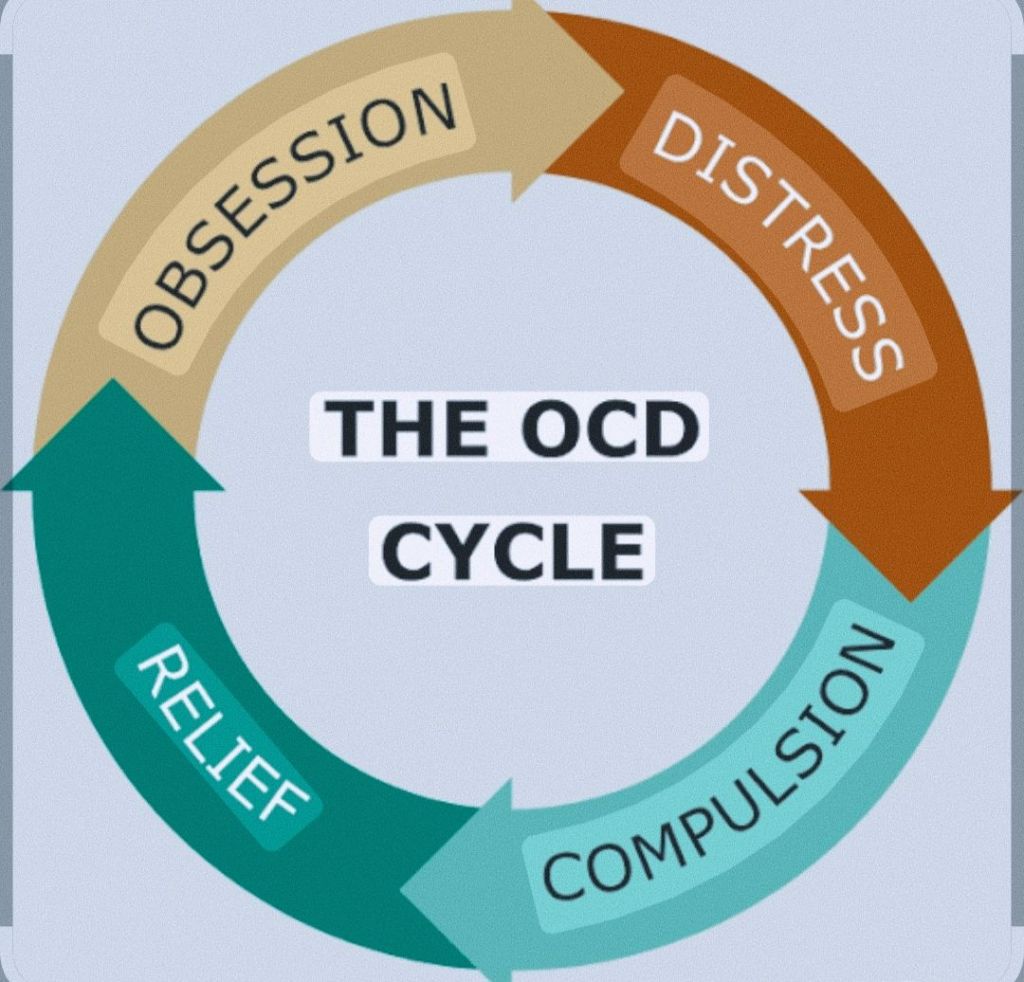

She scrubs the floor until her knuckles bleed. She checks the gas knob thirteen times before stepping out. And when she finally gathers the courage to tell someone about it, she’s dismissed as just being a “good wife.” Welcome to the silent epidemic that thrives behind rangolis and rituals—Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) among Indian women.

The statistics claim that only 0.6% of Indians suffer from OCD. But this number isn’t comforting—it’s damning. It doesn’t signal good mental health; it signals a national blind spot. In contrast, the global average sits at 2–3%, and Western societies at least attempt to confront it. In India, especially among women, OCD is swept under the rug—hidden behind spotless kitchens and color-coordinated spice racks. It’s not that the illness doesn’t exist. It’s that it’s being lived out silently, misdiagnosed, or never diagnosed at all.

In India, OCD doesn’t look like what we imagine from psychology textbooks. It doesn’t always involve obsessive thoughts about harming someone or touching door handles. Instead, it appears as relentless cleaning, compulsive caregiving, excessive checking, and self-punishing rituals. And while this is a medical disorder, society often dresses it up as virtue. A woman who stays up all night scrubbing a clean home isn’t seen as mentally ill—she’s praised as the ultimate caregiver. That’s not just a misunderstanding. That’s a cultural gaslight.

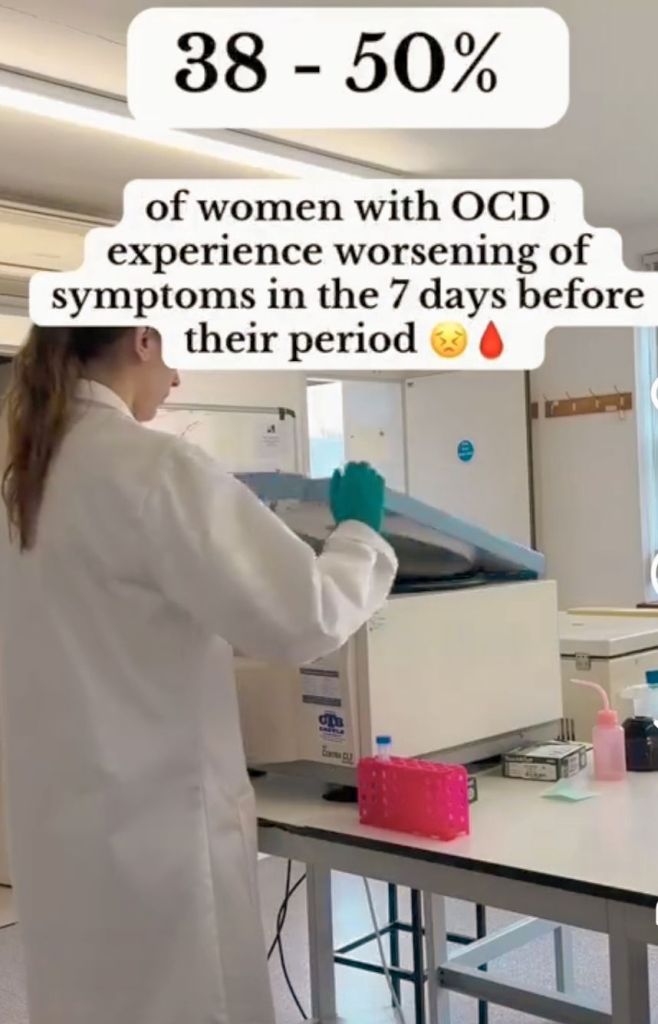

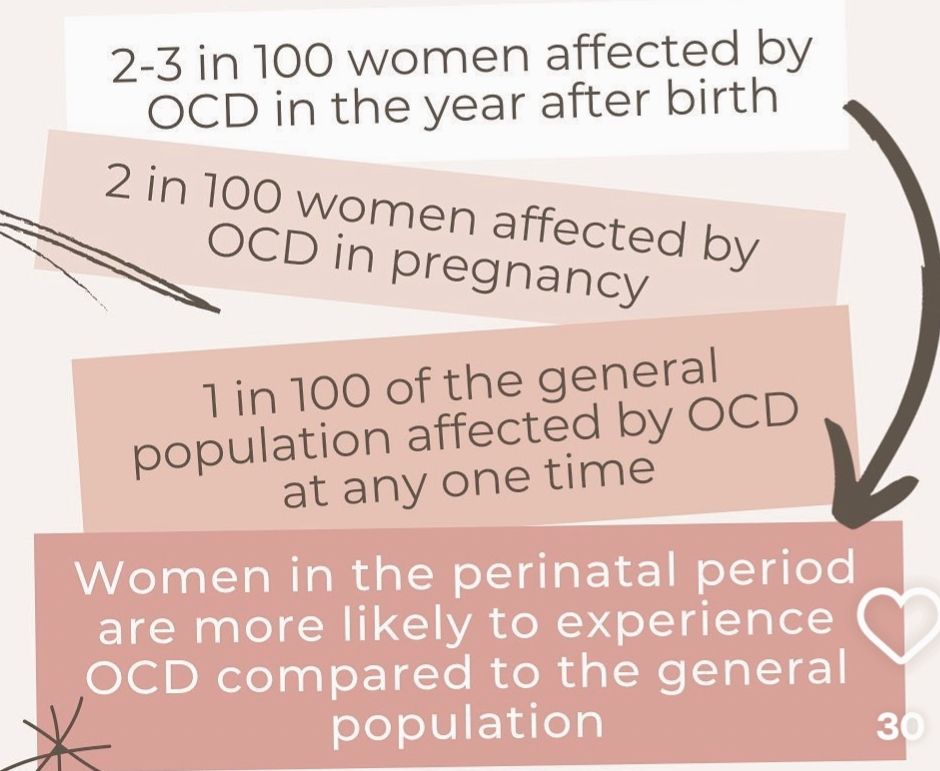

Indian women suffer from OCD in deeply gendered ways. Hormonal changes during menstruation, pregnancy, postpartum periods, and menopause make them biologically more vulnerable to anxiety and compulsive behaviors. Socially, they’re buried under an avalanche of expectations—to be good daughters, perfect wives, flawless mothers, and dutiful daughters-in-law. OCD thrives in this pressure cooker of performance. While men may obsess over symmetry or religious morality, women spiral into cleanliness, control, and guilt. Add to that domestic violence, infertility, dowry stress, and caregiving burnout, and OCD becomes not a quirk but a collapse.

The suffering doesn’t stop at the compulsion—it continues in the silence that follows. In rural areas, India has fewer than one psychiatrist per lakh of population. Even in cities, access is skewed. Most women don’t have financial independence, autonomy, or social support to seek help. Their physical symptoms—fatigue, aches, and breathlessness—are dismissed or misdiagnosed. The mind is in crisis, but it speaks through the body. Years of social conditioning have trained women to not talk about their pain. So, it festers in private, often manifesting as somatic distress. And when they do speak up, they’re told they’re just “too sensitive” or “doing too much.”

The romanticization of sacrifice is the deadliest part. OCD gets sugar-coated in phrases like “perfectionist,” “superwoman,” or “always on her feet.” These aren’t compliments. They’re symptoms. A spotless house should not come at the cost of shredded nerves. A meal served on time should not mean hours of anxiety. Yet in India, the very compulsions that should prompt psychiatric evaluation are celebrated as signs of womanly dedication. We’ve built a culture that prefers pretty façades to uncomfortable truths.

Still, there are islands of hope in this ocean of neglect. Kerala’s decentralized mental health initiatives empower panchayats to provide localized care. Tamil Nadu’s mobile mental health vans and community radio programmes are breaking stigma in unreachable corners. Goa integrates perinatal mental health with general healthcare, and Maharashtra has launched vocational and therapeutic services specifically for women with psychiatric needs. Karnataka’s NIMHANS Digital Academy is even training community health workers to deliver therapy through smartphones. These examples prove that transformation is possible—not just in clinics but within communities.

But to address this crisis systemically, policy must evolve. Mental health’s share in the Union Budget must rise from its abysmal 1.93% to at least 5%. Mental healthcare should be built into every scheme targeted at women—from Janani Suraksha Yojana to Beti Bachao. Diagnostic tools must reflect gendered patterns. ASHA workers should be trained to recognize OCD during routine visits. Self Help Groups must double as peer mental health circles. Women should not have to choose between being seen and being sane.

We must also shift the lens through which we view women’s suffering. That obsessively clean kitchen might be a silent scream. That ‘model wife’ who wakes at 4 a.m. to sterilize her baby’s bottles for the fifth time is not “just being careful.” She may be breaking. And she deserves care, not applause.

OCD among Indian women is not just a mental health issue—it’s a feminist reckoning, a social justice imperative, and a call to re-examine how deeply our culture confuses pain with piety. For too long, we’ve forced women to wear their illness like a badge of honour. It’s time to let them be messy. To let them be imperfect. To let them be unwell without being unloved, unheard, or unseen.

Let her wash her hands because she wants to—not because her illness, her family, or her upbringing insists on it. Let her compulsions be recognized for what they are: symptoms, not sacrifices.

Mental illness is not tradition. And silence is not virtue.

Visit arjasrikanth.in for more insights

One response to ““Mangalsutra, Mehendi, and Madness: The Untold OCD Epidemic Among Indian Women””

We need more awareness.

LikeLike