India is building world-class assembly lines without assembling beds. Until worker housing becomes policy—not charity—our manufacturing dreams will remain sleepless.

India is in the throes of a manufacturing revolution, a high-voltage sprint to become the factory of the world. From assembling iPhones to stitching garments for global brands, the “Make in India” campaign is shifting from hashtag to hardware. Industrial zones are humming, policies are aligned, investors are betting big—and yet, in the roaring engine room of India’s manufacturing story, one critical gear remains rusted and forgotten: worker housing.

We’re not talking about fringe benefits here. We’re talking about beds. About roofs. About a basic, inescapable fact of industrial growth: factories don’t run on steel and silicon—they run on people. And those people need a place to sleep.

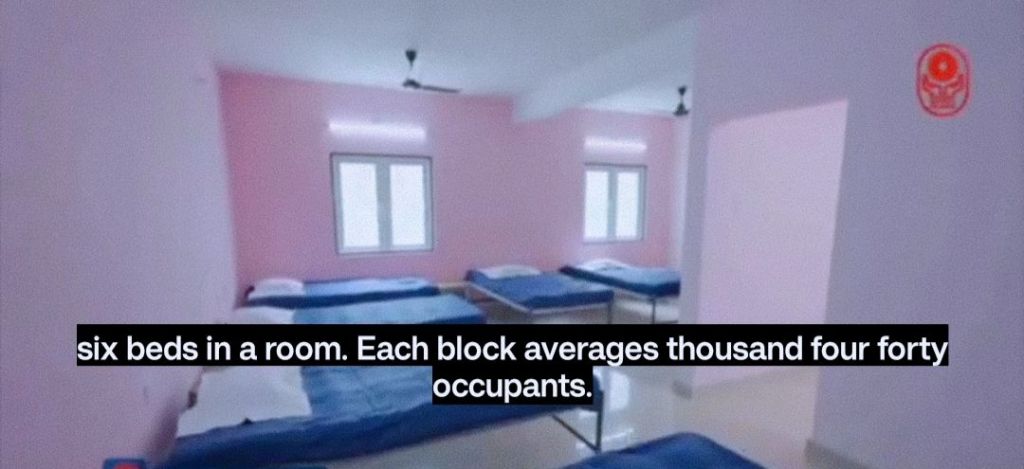

Consider Foxconn in Tamil Nadu. Everyone talks about the scale of its investment, the thousands of jobs created, and the geopolitical chessboard of electronics supply chains. But here’s the real kicker: Foxconn had to spend over $230 million to build housing for 18,000 workers before it could make a single device. Not out of charity, but out of necessity. Because without dorms, there are no workers. Without workers, there is no output. Without output, there is no factory. This isn’t an afterthought; this is the bedrock.

Historically, smart nations have understood this. The UK’s Bournville wasn’t just home to Cadbury chocolate—it was a masterclass in how good housing boosts good business. In the early 20th century, the Bata family famously built entire towns for their shoemakers, including Batnagar in West Bengal. But it was Asia—particularly China and Taiwan—that cracked the code. They embedded housing into their industrial policy. Foxconn’s Chinese operations included not just factories but entire mini-cities with dorms, clinics, and shopping complexes. These were not extras. These were essentials.

India flirted with this model once. Bokaro, Bhilai—entire public sector steel towns were built with housing baked into their blueprints. But as private enterprise took over the industrial baton, worker housing quietly fell off the agenda. Today, most of India’s factory workers live in overcrowded, unsafe, informal settlements. In Delhi’s garment district, workers cough up ₹3,000 a month to share a windowless room with four or five others. That’s nearly half their income, spent not on comfort, but proximity. They stay not because it’s livable, but because it’s bearable.

Why has worker housing become the invisible crisis in India’s industrial growth story? Because nobody sees money in it. Workers can’t afford high rents. Informal landlords offer bottom-rung solutions. And private developers steer clear because the math doesn’t work. Factor in India’s construction delays (almost 50% of projects run late), poor rental yields (a measly 2.3%), and a regulatory jungle that changes from state to state—and you’ve got a cocktail of apathy and paralysis.

The government did try to fix this. In 2020, it launched the Affordable Rental Housing Complexes (ARHC) scheme. Two shiny models: retrofit unused government housing, or let private players build dorms with a 25-year lease. The result? Underwhelming. Less than 7% of target conversions materialised. A mere 35,000 beds were built under the private model—many far from actual industrial hubs. Good intent, abysmal delivery.

Meanwhile, some isolated wins shine through. In Tirupur, Tamil Nadu, garment exporters and local authorities have worked together to create worker housing. Gujarat’s Sanand cluster boasts dorms backed by public-private efforts. Even CSR budgets are being creatively deployed—Rustomjee in Mumbai built 35,000 square feet of worker accommodation this year alone. But these are outliers, not the norm. They succeeded not because of policy, but in spite of it.

To truly industrialise at scale, India must get serious about workforce housing. That starts with a mindset shift. Housing is not welfare—it is infrastructure. It must be planned along with roads, electricity, and water. Land-use regulations must allow mixed-use zones. Financial incentives must make it worthwhile for developers. And most importantly, housing must be baked into every new manufacturing project’s blueprint—not as a CSR checkbox, but as a non-negotiable requirement.

We say our cheap labour is a competitive advantage. But cheap labour that’s homeless, overworked, and humiliated is a ticking time bomb. Imagine a young woman from Jharkhand who moves to a textile hub with big hopes, only to sleep in a room with no door, no safety, and a toilet shared with 30 others. She doesn’t last long. She shouldn’t have to.

The next time a foreign company lands in India to start a factory, we should ask more than just: “How much land do you need?” or “What subsidy are you looking for?” We should ask: “Where will your workers live? Will they have a room with a door that locks? A place to rest with dignity?”

Because here’s the truth: India can’t manufacture its future if it won’t house its present. Make in India won’t work if those who make it sleep in slums. You can’t build a world-class economy on the backs of people who have nowhere to sleep.

No beds, no bytes. No rooms, no robots. No homes, no hope.

Make in India needs a mattress—before it needs a machine.

And until we realise that, we’re just building factories full of ghosts.

Visit arjasrikanth.in for more insights