Bombs, Blood, and Backlash: The Strategic Bankruptcy of Terror

Terrorism, often employed by extremist actors to advance ideological, political, or religious agendas, is a strategy rooted in coercion through fear and violence. While such acts may temporarily destabilize societies or capture global attention, their long-term efficacy remains deeply questionable. A survey of modern and historical conflicts reveals that terrorism is not merely a morally reprehensible tactic—it is also strategically flawed. Rather than catalyzing meaningful change, terrorism often precipitates a range of counterproductive consequences: state repression, loss of public sympathy, internal organizational disintegration, and socio-economic devastation.

At its core, terrorism fundamentally undermines the legitimacy of the very causes it purports to champion. The indiscriminate targeting of civilians erodes public support, not just from the broader society but often from within the very communities these groups claim to represent. The Irish Republican Army (IRA), once a formidable insurgent force, faced an irreversible decline in public support following the 1998 Omagh bombing that killed 29 civilians. That tragic event shifted the public discourse, undermining any residual sympathy and delegitimizing the armed struggle in favor of political negotiation and democratic engagement.

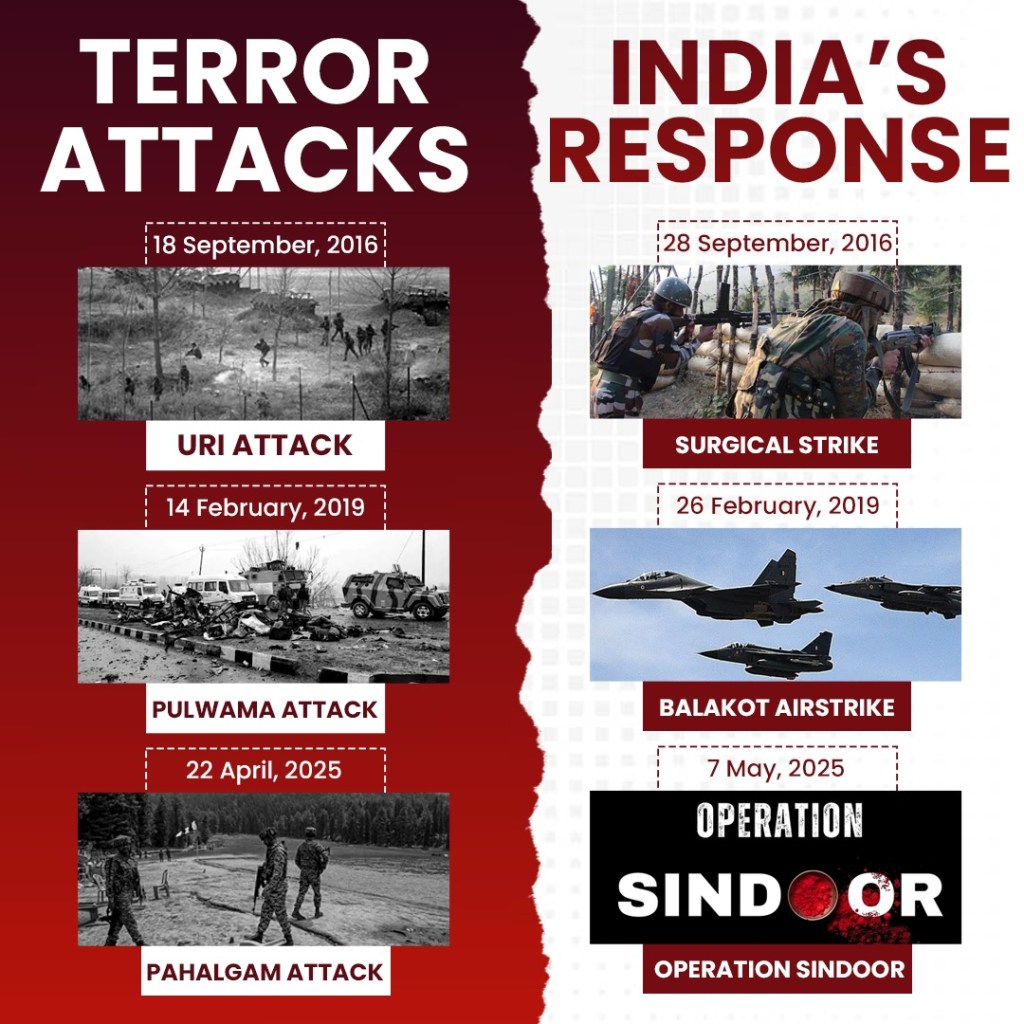

Empirical research supports the notion that acts of terror rarely yield favorable political outcomes. Civilians, when targeted, tend to respond not with acquiescence but with heightened resistance, a phenomenon social scientists describe as the “rally-around-the-flag” effect. Instead of weakening state structures, terrorism frequently galvanizes national unity, justifying expansive counter-terrorism measures and the consolidation of state power. The global response to the September 11, 2001 attacks offers a salient example. The U.S. responded with overwhelming military and intelligence campaigns that led to the dismantling of Al-Qaeda’s operational capabilities and the eventual killing of its leader, Osama bin Laden.

Similarly, Sri Lanka’s decisive military campaign against the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in 2009 effectively ended a decades-long insurgency, albeit with significant humanitarian concerns. In both cases, terrorism failed to achieve its desired political objectives and instead catalyzed a coercive state backlash, reinforcing the status quo.

Statistical analyses of terrorist movements reinforce this narrative of strategic inefficacy. Studies suggest that less than 7% of terrorist campaigns achieve their stated political goals. Groups like Hamas, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), and the Red Brigades in Italy have engaged in violent campaigns for decades, yet have secured few, if any, substantive policy victories. Their actions have often hardened opposition rather than inspiring dialogue, underscoring the tactical ineffectiveness of violence as a means of negotiation.

Organizationally, terrorist movements are often plagued by internal divisions, ideological schisms, and leadership vacuums. The Islamic State’s rapid ascent and equally rapid collapse highlight this instability. Following the loss of key leaders such as Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and the erosion of territorial control, the group splintered into disorganized factions. Al-Qaeda, too, struggled to maintain coherence following the death of bin Laden. Such fragmentation limits these groups’ capacity to maintain momentum, erodes morale, and diminishes their political leverage.

Beyond strategic failure, terrorism imposes catastrophic socio-economic consequences on both targeted and origin communities. In Nigeria, Boko Haram’s decade-long insurgency has claimed over 300,000 lives and displaced millions, plunging regions into chronic underdevelopment without achieving any semblance of Islamic governance or political reform. In Afghanistan, the Taliban’s return to power followed two decades of destructive insurgency that left the nation economically debilitated and diplomatically ostracized. Far from ushering in utopia, these campaigns have entrenched poverty, trauma, and isolation.

Yet, despite this grim track record, terrorism persists. This endurance can be attributed to several factors. First, terrorism has symbolic value—its shock appeal provides a potent propaganda tool, particularly when disseminated via social media, as seen in ISIS’s sophisticated digital outreach. Second, political marginalization often drives disenfranchised groups to seek violent alternatives when peaceful avenues appear blocked. Third, state sponsorship of terrorism as a tool of proxy warfare, notably in the case of Iran-backed Hezbollah, sustains these movements despite their failures on the ground.

In conclusion, terrorism is not only an immoral tactic but also an ineffective one. Its ability to disrupt is indisputable, yet its capacity to deliver sustainable political change is negligible. Historical and contemporary evidence overwhelmingly illustrates that terrorism strengthens state mechanisms, alienates potential supporters, and fractures the very movements it is meant to empower. Lasting change is realized not through bombs and bullets, but through the arduous processes of dialogue, reform, and inclusive governance. The irony of terrorism lies in its tragic inversion: in seeking to dismantle unjust systems, it often fortifies them, leaving behind not revolution, but ruins.

Visit arjasrikanth.in for more insights